![]() The Byzantine Empire was certainly one of the most interesting medieval states. Due to its location, its culture and art, it combines both European and Middle Eastern influences. That bond created specific forms and mentality, which differed it from the rest of European states of that time.

The Byzantine Empire was certainly one of the most interesting medieval states. Due to its location, its culture and art, it combines both European and Middle Eastern influences. That bond created specific forms and mentality, which differed it from the rest of European states of that time.

Icons

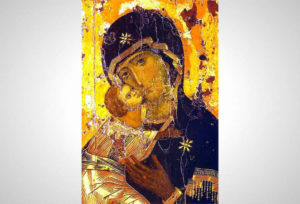

One of the most distinctive branches of Byzantine art are icons, which represented either Christ, Virgin Mary or one of the saints. They were always represented in such manner as being out of this world, and the believers treated them as objects through which they could connect with God. The backgrounds on the icons were always colored golden, which represented negation of time and space, thus adjusting the focus only on the displayed character, who was often represented with a calm, neutral facial expression, eyes focused on the observer.

Icon Development

![]() The worship of icons has probably developed from the relic cult that appeared in the East in 4th century. 1 The believers wanted to be closer to certain saints, as to Christ and Virgin Mary themselves. This was achieved through solid objects which were, during their lifetime, in some physical relation to them. Icons had a same purpose, they represented saints, and the believers attributed them miraculous powers; they even considered some of the icons not to be painted by human hand. The earliest preserved individual icons originated in the 5th and 6th century. Most of them come from a monastery of St. Catherine on the hill of Sinai. Other preserved specimen primarily originate from 10th and 11th century, but the real bloom of icons is considered to be during the Palaeologus dinasty (13th-15th century), and not just in Byzantium, but also on the territories of Bulgaria and Russia.2

The worship of icons has probably developed from the relic cult that appeared in the East in 4th century. 1 The believers wanted to be closer to certain saints, as to Christ and Virgin Mary themselves. This was achieved through solid objects which were, during their lifetime, in some physical relation to them. Icons had a same purpose, they represented saints, and the believers attributed them miraculous powers; they even considered some of the icons not to be painted by human hand. The earliest preserved individual icons originated in the 5th and 6th century. Most of them come from a monastery of St. Catherine on the hill of Sinai. Other preserved specimen primarily originate from 10th and 11th century, but the real bloom of icons is considered to be during the Palaeologus dinasty (13th-15th century), and not just in Byzantium, but also on the territories of Bulgaria and Russia.2

Over time, especially during the iconoclasm period, various types of icons have developed. One of those types is, for example, „Calendar icons“, which depicted religious feasts through a certain period of time. Some of them displayed groups of several dozen saints, systemized in a couple of rows. One other common kind were so-called „Vita icons“, which, apart from the central saint figure, also represented images from the saint’s life.

The Function Of Icons

Icons were, as a material medium between the believers and God, used in several ways. They had an important liturgical role; masses were held in front of an icon that represented the respective feast. Each church had an icon depicting its saint protector, whom it was dedicated to. Also, portable icons, painted on a canvas or a wooden pad, had an important role in processions. Apart from this, public, icons also had a private, more intimate significance. Many believers had their own personal icons they used in domiciliary pieties, or during travels.3

Icons were, as a material medium between the believers and God, used in several ways. They had an important liturgical role; masses were held in front of an icon that represented the respective feast. Each church had an icon depicting its saint protector, whom it was dedicated to. Also, portable icons, painted on a canvas or a wooden pad, had an important role in processions. Apart from this, public, icons also had a private, more intimate significance. Many believers had their own personal icons they used in domiciliary pieties, or during travels.3

The number of icons in churches grows through time, so they are first displayed on templon, which later became iconostasis, later used as a barrier between the sanctuary and the public part of the church. The order of the icons on iconostasis was strictly determined, and most often it consisted of five levels.4

Iconoclasm

The worship of icons started in the beginning of the 8th century, particularly among commoners, and it quickly adopted excessive proportions. People talked to icons, and some were considered not to be made by humans. They were attributed all kinds of supernatural powers.5

![]() A propaganda against the depiction of saints, Christ or Virgin Mary in paintings followed as a reaction, and it lasted for over than one hundred years (726-843). Icons were burnt publicly, and frescos and mosaics were also destroyed. But, it seemed that the reasons for iconoclasty were not purely of religious, but also political nature. In Byzantium, the anti-paiting propaganda started in 726, which corresponds to the time when caliph Yazid II ordered all the paintings in temples, churches and houses destroyed.6 Certain influences of ideas from the Middle East can indeed be recognized in iconoclasm, which is also obvious by the origin of emperors that were its most acclaimed supporters. Iconoclasm was started by emperor Leo III who was of Syrian origin, and after a short pause, it was restarted by emperor Leo V who was Armenian. This old dispute between Greek and Oriental elements of Byzantine culture can additionaly be confirmed by the names of the empresses who have reestablished the cult of paintings; these were empress Irene of Greece and empress Theodora of Paphlagonia.7

A propaganda against the depiction of saints, Christ or Virgin Mary in paintings followed as a reaction, and it lasted for over than one hundred years (726-843). Icons were burnt publicly, and frescos and mosaics were also destroyed. But, it seemed that the reasons for iconoclasty were not purely of religious, but also political nature. In Byzantium, the anti-paiting propaganda started in 726, which corresponds to the time when caliph Yazid II ordered all the paintings in temples, churches and houses destroyed.6 Certain influences of ideas from the Middle East can indeed be recognized in iconoclasm, which is also obvious by the origin of emperors that were its most acclaimed supporters. Iconoclasm was started by emperor Leo III who was of Syrian origin, and after a short pause, it was restarted by emperor Leo V who was Armenian. This old dispute between Greek and Oriental elements of Byzantine culture can additionaly be confirmed by the names of the empresses who have reestablished the cult of paintings; these were empress Irene of Greece and empress Theodora of Paphlagonia.7

The most prominent of iconoclasm supporters were intelectuals, while the further worshipping of paintings was mostly advocated by the common folk, headed by monks. Numerous monks, with their large estates, rich treasuries, and exceptional influence on the commoners were an extraordinary powerful force within the state. Because of their power and influence, the emperors used the iconoclastic struggle for a chance to diminish their power, and also seize part of their possessions. Thus, alongside religious and political, iconoclasm also had a social context.8

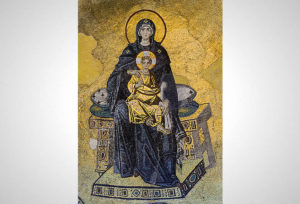

The conflict lasted from 726 to 780 when empress Irene, who seized the throne on behalf of her underage son, upon agreement with the pope managed to reestablish the cult of worshipping paintings (II Nicaea Council, 787).9 However, in 813 emperor Leo V restarted the anti-painting campaign, which lasted for another thirty years, all until 843 when empress Theodora finally confirmed authenticity of the canon from 787 AD.10 The final end of iconoclasm was celebrated by a ceremonial procession to Hagia Sophia, led by empress Theodora. New mosaics in Hagia Sophia have been painted later on, among which the one depicting Virgin Mary holding the Christ, located in the apse of the church, is particularly outstanding.11

The conflict lasted from 726 to 780 when empress Irene, who seized the throne on behalf of her underage son, upon agreement with the pope managed to reestablish the cult of worshipping paintings (II Nicaea Council, 787).9 However, in 813 emperor Leo V restarted the anti-painting campaign, which lasted for another thirty years, all until 843 when empress Theodora finally confirmed authenticity of the canon from 787 AD.10 The final end of iconoclasm was celebrated by a ceremonial procession to Hagia Sophia, led by empress Theodora. New mosaics in Hagia Sophia have been painted later on, among which the one depicting Virgin Mary holding the Christ, located in the apse of the church, is particularly outstanding.11

The Consequences Of Iconoclasm

During the iconoclastic campaigns, the Byzantine Empire was weakened economically and militarily. However, this was only temporary, since the Empire came out of iconoclasm enriched, mostly because of the seized treasure from the churches’ treasuries. Nevertheless, the relations with the West were also disrupted, since the reasons for iconoclastic campaigns and ruination of sacral paintings were noncomprehending in the Western society.

In a little more than one hundred years of this movement, many earlier artworks have been destroyed, and artistic continuity was abrupted. Still, this crisis brought a new swing in art, since iconoclastic art turned to natural and secular scenery. All of this brought a new renascence to the art itself, which would particularly be possible to sense in the centuries to come.12

Other articles from the series: “The Art of Byzantium”

- To some icons supernatural powers was devoted. It was considered that they are crying, and that they are not made by human hand. They could be godfathers at baptism, and the soldiers where able to carry them to war.

- Iconophiles considered paintings which were made on top of the icons, equally dreadful as crucifixion of Christ.

- Vadim JELISEJEV, Jean NAUDOU, Gaston WIET, Philippe WOLFF, Historija čovječanstva: Kulturni i naučni razvoj, book III, Velike civilizacije srednjeg vijeka, Naprijed, Zagreb, 1972

- Thomas F. MATHEWS, Byzantium, From Antiquity to the Renaissance, Perspectives Prentice Hall, Inc. I Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 1998

- Ania SKLIAR, Bizant, Extrade d.o.o., Rijeka, 2005

- 1 Ania SKLIAR, Bizant, Extrade d.o.o., Rijeka, 2005, 98.

- 2 Ania SKLIAR (note 1), 99.

- 3 Ania SKLIAR, (note 1), 99.

- 4 Thomas F. MATHEWS, Byzantium, From Antiquity to the Renaissance, Perspectives Prentice Hall, Inc. I Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 1998, 59-60.

- 5 Usp. THOMAS F. MATHEWS (note 4), 18-21

- 6 Which the Emperor Theodosius closed at the end of the fourth century.

- 7 Vadim JELISEJEV, Jean NAUDOU, Gaston WIET, Philippe WOLFF, Historija čovječanstva: Kulturni i naučni razvoj, svezak III, Velike civilizacije srednjeg vijeka, Naprijed, Zagreb, 1972, 181.

- 8 Vadim JELISEJEV, Jean NAUDOU, Gaston WIET, Philippe WOLFF, (note 5), 181.

- 9 Vadim JELISEJEV, Jean NAUDOU, Gaston WIET, Philippe WOLFF, (note 5), 182.

- 10 Thomas F. MATHEWS, (note 4), 57-58.

- 11 Vadim JELISEJEV, Jean NAUDOU, Gaston WIET, Philippe WOLFF, (note 5), 182.

Your comment