The Crusades

The Holy Land, along with the places of Christ’s life and torment, were popular destinations to pilgrims since the very beginnings of Christianity. The conquest of the Holy Land by the Muslims posed a threat to the safety of Christian pilgrims. The European monarchs have an idea to take back the Holy Land from the infidels, and the Pope sends a call to a crusade. The Crusades lasted from the end of 9th century to the end of 13th century. Not only did the Crusades mobilize the Christian masses in the West, but they also opened a new space for market, travel and getting touch with different cultures. It was a time of an uprise of knighthood, so it is no wonder that the ideal of a medieval man merged with another ideal: monkhood. This dual calling was actualized through knight orders, and one of the most prominent was the Order of the Knights Templar.1

The Holy Land, along with the places of Christ’s life and torment, were popular destinations to pilgrims since the very beginnings of Christianity. The conquest of the Holy Land by the Muslims posed a threat to the safety of Christian pilgrims. The European monarchs have an idea to take back the Holy Land from the infidels, and the Pope sends a call to a crusade. The Crusades lasted from the end of 9th century to the end of 13th century. Not only did the Crusades mobilize the Christian masses in the West, but they also opened a new space for market, travel and getting touch with different cultures. It was a time of an uprise of knighthood, so it is no wonder that the ideal of a medieval man merged with another ideal: monkhood. This dual calling was actualized through knight orders, and one of the most prominent was the Order of the Knights Templar.1

The Founding of the Order of the Templars

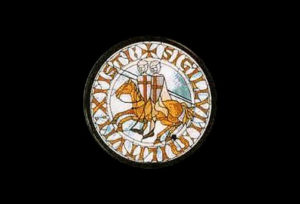

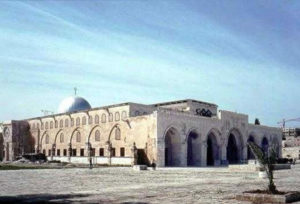

The knights order of the Templars was founded in 1119 in Jerusalem on the initiative of two French knights Huges de Payens and Geoffray de Saint-Omer. Their idea was to start a knights order that would protect pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem, against Muslim attacks. Baudoin II, King of Jerusalem, gave them a palace next to the former Temple of Solomon, therefore the Brethren called themselves Knights of the Temple of Solomon (Fratres militiae Templi Salomonis), or Templars in short.2 Over the first nine years of existence, their numbers slowly grew, and in 1128 there were fourteen of them. The same year they were officially endorsed by the Holy See at the council in Troyes. The templars used the Rule of St. Benedict as their code. After the official acknowledgment from the Holy See, the Order of the Knights Templar grew rapidly.

The knights order of the Templars was founded in 1119 in Jerusalem on the initiative of two French knights Huges de Payens and Geoffray de Saint-Omer. Their idea was to start a knights order that would protect pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem, against Muslim attacks. Baudoin II, King of Jerusalem, gave them a palace next to the former Temple of Solomon, therefore the Brethren called themselves Knights of the Temple of Solomon (Fratres militiae Templi Salomonis), or Templars in short.2 Over the first nine years of existence, their numbers slowly grew, and in 1128 there were fourteen of them. The same year they were officially endorsed by the Holy See at the council in Troyes. The templars used the Rule of St. Benedict as their code. After the official acknowledgment from the Holy See, the Order of the Knights Templar grew rapidly.  More and more noblemen joined their cause, and they also received numerous donations, mostly as land properties. Holy Bernard participated in the creation of templar rules which were summarized in 75 articles, and very similar to the rules of the Cistercian Order, of which its author was a member. The rules regulated clothing and equipment, a knight’s activities from the moment he wakes up until the prayer before lying to bed, internal hierarchy, and military behaviour. Pope Innocent II confirmed the institution of the Order in 1139 by his bull entitled „Omne datum optimum“. From then, the Order of the Templars spreaded even faster, so in 1147 just in Jerusalem there were 350 knights and around 2000 brethren in different services.3

More and more noblemen joined their cause, and they also received numerous donations, mostly as land properties. Holy Bernard participated in the creation of templar rules which were summarized in 75 articles, and very similar to the rules of the Cistercian Order, of which its author was a member. The rules regulated clothing and equipment, a knight’s activities from the moment he wakes up until the prayer before lying to bed, internal hierarchy, and military behaviour. Pope Innocent II confirmed the institution of the Order in 1139 by his bull entitled „Omne datum optimum“. From then, the Order of the Templars spreaded even faster, so in 1147 just in Jerusalem there were 350 knights and around 2000 brethren in different services.3

The Expansion and Development of the Order

From Jerusalem, the templars spread all over Europe, and found their first European center in Paris, which, over time, becomes the headquarters of the templar order. Following that, they establish templar provinces all over Europe.4 The expansion of the templar web throughout European countries was also improved by the fact that they themselves realized that the Holy Land didn’t offer much opportunity of succesful operation and existence, so they established their European headquarters in Paris in 1147. By arriving to Europe, they became one of the orders of the western Christian world, but having one special advantage: along with the standard monk virtues (obedience, purity, poverty), they had one that was most modern at that time: knighthood. This makes their rapid expansion throughout Europe in the second half of the 12th and the 13th century completely understandable.5

From Jerusalem, the templars spread all over Europe, and found their first European center in Paris, which, over time, becomes the headquarters of the templar order. Following that, they establish templar provinces all over Europe.4 The expansion of the templar web throughout European countries was also improved by the fact that they themselves realized that the Holy Land didn’t offer much opportunity of succesful operation and existence, so they established their European headquarters in Paris in 1147. By arriving to Europe, they became one of the orders of the western Christian world, but having one special advantage: along with the standard monk virtues (obedience, purity, poverty), they had one that was most modern at that time: knighthood. This makes their rapid expansion throughout Europe in the second half of the 12th and the 13th century completely understandable.5

The Order of the Knights Templar had a very strictly defined internal hierarchy. Every province had a chief known as magister. All provinces and all possessions were subdue to the „general capitul“, a congregation of chiefs that solely had the authority to nominate magisters. Chief of the entire order was called the grand magister („the Grand Master“). Second in command was senechal who was Grand Master’s procurator. Marshal was chief in command of the army.6

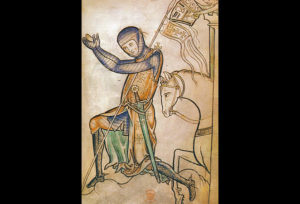

The Templars divide into several groups: the knights templar, the lower-born sergeants, the turcopoles, and the non-military brethren (craftsmen, doctors, chefs, administrators e.a.). The knights templar could only become members of the higher aristocracy. They wore a white surcoat as a sign of purity. In 1147, Pope Eugenius III granted them the right to wear a red cross as a symbol of martyrs’ blood. The red crosses were depicted not only on their surcoats, but on their shields as well. Their equipment included a chain mail, helmet, lower-leg visors, naval spear, sword, Turkish hammerhead, shield, and three knives of the same size. The lower-born seargents were templar warriors that weren’t knighted. Unlike the knights, they wore black surcoats with red cross. They wore helmets on their heads, and their shields were colored black with red cross on them. They also had arbalests. Over the two centuries of their existance, the templars developed a recognizable insignia consisting of three colors: white, black and red. The black represented religion, and was depicted at the top in their flags. The white symbolized spiritual purity, and the red cross symbolized the blood of Christ.

The Templars divide into several groups: the knights templar, the lower-born sergeants, the turcopoles, and the non-military brethren (craftsmen, doctors, chefs, administrators e.a.). The knights templar could only become members of the higher aristocracy. They wore a white surcoat as a sign of purity. In 1147, Pope Eugenius III granted them the right to wear a red cross as a symbol of martyrs’ blood. The red crosses were depicted not only on their surcoats, but on their shields as well. Their equipment included a chain mail, helmet, lower-leg visors, naval spear, sword, Turkish hammerhead, shield, and three knives of the same size. The lower-born seargents were templar warriors that weren’t knighted. Unlike the knights, they wore black surcoats with red cross. They wore helmets on their heads, and their shields were colored black with red cross on them. They also had arbalests. Over the two centuries of their existance, the templars developed a recognizable insignia consisting of three colors: white, black and red. The black represented religion, and was depicted at the top in their flags. The white symbolized spiritual purity, and the red cross symbolized the blood of Christ.

Aside fighting the infidels and providing protection for the pilgrims, the templars developed an abundant economic activity. They practised banking, and lent money for interest. They were charging spiritualistic and secular services. They were also employed as civil servants, i.e. they often worked for popes and kings. They were exceptionally reliable, because they worked in the order’s best interest, and not in the interest of particular dinasties. In time, they became more wealthy and powerful than any ruler, which is why they gained many enemies.

The Dissolution of the Order

At the peak of their glory the templars owned over nine thousand estates, supposedly along with 3,000 castles, fortifications and other buildings. The order had up to twenty thousand members. Just in the Temple in Parisian headquarters resided around 4,000 knights and other brethren. The purpose of the Order’s existance came to question after the fall of Acre, the last Christian stronghold in Jerusalem, in 1291. It was then suggested that the Knigths Templar should unite with the Knights Hospitaller, but the Templars weren’t interested in such a union.7

At the peak of their glory the templars owned over nine thousand estates, supposedly along with 3,000 castles, fortifications and other buildings. The order had up to twenty thousand members. Just in the Temple in Parisian headquarters resided around 4,000 knights and other brethren. The purpose of the Order’s existance came to question after the fall of Acre, the last Christian stronghold in Jerusalem, in 1291. It was then suggested that the Knigths Templar should unite with the Knights Hospitaller, but the Templars weren’t interested in such a union.7

French king Philip the Fair taught of the templars as a threat, and, besides, he needed money. He had tried to join the Templars himself, but was refused. He falsely accused them, and on October 13th, 1307 he ordered Templars all over France to be arrested and thrown into dungeons. 140 templars in France were brutally tortured and killed. The Grand Master Jacques de Molay was burnt at the stake in Paris, March 18th, 1314. The knights order of the Templars was dissolved at the council of Vienne, April 3rd, 1312. The pope managed to save the Templars’ assets from the hands of Philip the Fair, thus they were granted to the Knights Hospitaller.8

Next article in these series

- Baudoin II, King of Jerusalem, gave them a palace next to the former Temple of Solomon, therefore the Brethren called themselves knights of the Temple of Solomon (Fratres militiae Templi Salomonis), or templars in short

- The templars’ European headquarters were in Paris

- Aside fighting the infidels and providing protection for the pilgrims, the templars practised banking, and lent money for interest

- At the peak of their glory the templars owned over nine thousand estates, supposedly along with three thousands castles, fortifications and other buildings. At that time the Order had up to twenty thousand members.

- Lelja DOBRONIĆ: Posjedi i sjedišta templara, ivanovaca i sepulkralaca u Hrvatskoj, Rad Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti, Zagreb, 1984.

- Lelja DOBRONIĆ: Viteški redovi, templari i ivanovci u Hrvatskoj, Kršćanska sadašnjost, Zagreb, 1984.

- Lelja DOBRONIĆ: Templari i ivanovci u Hrvatskoj, Dom i svijet, Zagreb, 2002.

- Mladen HOUŠKA (ur.): Templari i njihovo nasljeđe, 800 godina od dolaska templara na Zemlju sv. Martina (katalog izložbe), Muzej sv. Ivan Zelina, Sv. Ivan Zelina, 2009.

- Barbara FRALE: Templari, Profil, Zagreb, 2010.

- 1 Lelja DOBRONIĆ: Viteški redovi, templari i ivanovci u Hrvatskoj, Kršćanska sadašnjost, Zagreb, 1984., 15.

- 2 Mladen HOUŠKA (ur.): Templari i njihovo nasljeđe, 800 godina od dolaska templara na Zemlju sv. Martina (katalog izložbe), Muzej Sv. Ivan Zelina, Sveti Ivan Zelina, 2009., 7.

- 3 Usp. Mladen HOUŠKA (bilj. 2), 7.

- 4 u Francuskoj (Provansa, Francija-Ile de France, Poitou i Bourgogne), Engleskoj, Španjolskoj (Aragon, Katalonija, Kastilja), Portugalu, Italiji (Toscana, Lombardija, Sicilija – Apulija), Ugarskoj, Hrvatskoj i Njemačkoj (Magdeburg, Mainz)

- 5 Lelja DOBRONIĆ: Templari i ivanovci u Hrvatskoj, Dom i svijet, Zagreb, 2002., 27.

- 6 Mladen HOUŠKA (bilj. 2), 7.

- 7 Mladen HOUŠKA (bilj. 2), 12.

- 8 Mladen HOUŠKA (bilj. 2), 12-13.

Hey, very good read.

Thank you guys this was useful backround info for my novel!

Thanks alot for this info helped me alot. 😀