In the middle of the 9th century Franks and Byzantines were at the weakest point in their existence. Frankish Empire declines after Charlemagne departed, especially the death of his son and hear to the throne Louis the Pious. On the other hand Byzantium suffered in the ongoing conflict with the young Bulgarian state in rise, but also had problems on its eastern borders fighting with Arabic raiders. Problems in the back yard of two former medieval superpowers led the rulers of the state at the far corner of their interests zones to start acting more independent and with stronger self-confidence and reliance in their capabilities.

In the middle of the 9th century Franks and Byzantines were at the weakest point in their existence. Frankish Empire declines after Charlemagne departed, especially the death of his son and hear to the throne Louis the Pious. On the other hand Byzantium suffered in the ongoing conflict with the young Bulgarian state in rise, but also had problems on its eastern borders fighting with Arabic raiders. Problems in the back yard of two former medieval superpowers led the rulers of the state at the far corner of their interests zones to start acting more independent and with stronger self-confidence and reliance in their capabilities.

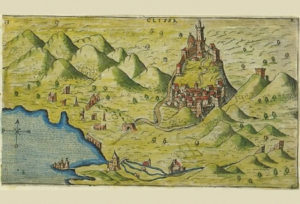

One of them who seized the opportunity in the time of crises was Croatian duke Trpimir who succeeded Mislav on the throne around 845 and ruled till 864. Trpimir acknowledged high power of Italic king and Frankish Emperor Lothar I. (840-855), but his reign shows the signs of truly independent local ruler. During him Croatia spread from rivers Sava and Kupa far to the south and river Cetina and from Adriatic sea to the east where the border line is situated on the river Drina.1 The center of state was situated in the castle of Klis.

Like all the rulers in this time period, he was a pious one and under a great influence of Catholic Church, the most organized institution in the region, and her clergy through which he received help for personal and state interests. His instituted pilgrimage with sons Petar, Zdeslav and Mutimir to Cividale, the center of Aquileian patriarchy and left us a written evidence of it on the pages of “Gospel of Cividale“. Another important evidence to support thesis for a strength of Trpimir Croatia in the time is an idea for the establishment of Diocese in Nin.2 Although it is hard to determine accurate day of its foundation, it’s certain that it didn’t belong under the jurisdiction of neither Rome or Constantinople but to Aquileian patriarchy, the center from where missionaries went on to baptist pagans in the Balkan.3

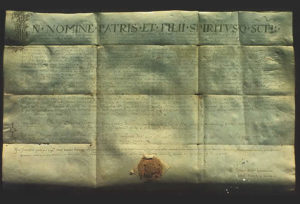

Trpimir decided to build the monastery and church in the proximity of his court in Klis, todays Rižinice near Solin. He invited Benedictines, prolongers of literacy, from Monte Cassino to Croatia. The meeting with Petar, archbishop of Split, took place in Bijaći, near Trogir on the land owned by Trpimir and the intention was to witness validity of paper, written by chaplain Martin, also known as Trpimir Beneficiary. With it Trpimir allowed archbishop to take claim on tenth from dukes property in Klis and confirms his legal ownership right over the church of St. George on Putalj in exchange for silver given by Trpimir to Benedictines for modification of villa rustica into monastery and for building a church in Rižinice. Inscription on the gable with his name on it says: PRO DUCE TREPIM[ERO]4 and in beneficiary Trpimir is called “with Divine support duke of Croats“ (dux Chroatorum munere divino),5 which makes this two monuments the oldest ones who mentioned the name of Croats and the title of the Croatian ruler.

Trpimir decided to build the monastery and church in the proximity of his court in Klis, todays Rižinice near Solin. He invited Benedictines, prolongers of literacy, from Monte Cassino to Croatia. The meeting with Petar, archbishop of Split, took place in Bijaći, near Trogir on the land owned by Trpimir and the intention was to witness validity of paper, written by chaplain Martin, also known as Trpimir Beneficiary. With it Trpimir allowed archbishop to take claim on tenth from dukes property in Klis and confirms his legal ownership right over the church of St. George on Putalj in exchange for silver given by Trpimir to Benedictines for modification of villa rustica into monastery and for building a church in Rižinice. Inscription on the gable with his name on it says: PRO DUCE TREPIM[ERO]4 and in beneficiary Trpimir is called “with Divine support duke of Croats“ (dux Chroatorum munere divino),5 which makes this two monuments the oldest ones who mentioned the name of Croats and the title of the Croatian ruler.

Social environment of the time carried a lot of influence from Ancient tradition. This is the reason why we find slaves on the property of Church on Mosor, close to Split. If we are aware of fact that in time of Trpimir’s beneficiary Church had slaves on Mosor, it is likely to deduct that Croatians rulers were donated the slaves to Archdiocese even before. The proof for this is citation in the text of beneficiary-stating how duke Mislav made such a offering to the clergy of Split’s Church.6

Social environment of the time carried a lot of influence from Ancient tradition. This is the reason why we find slaves on the property of Church on Mosor, close to Split. If we are aware of fact that in time of Trpimir’s beneficiary Church had slaves on Mosor, it is likely to deduct that Croatians rulers were donated the slaves to Archdiocese even before. The proof for this is citation in the text of beneficiary-stating how duke Mislav made such a offering to the clergy of Split’s Church.6

Another example which underlines importance of Trpimir is a quote from the text written by Gottshalk, member of the Benedictine Order, in which he titles Trpimir as „The King of Slavs“ (Rex Sclavorum). This is interesting because the use of royal title for the Croatian ruler is likely to be found in other scripts and texts of the period some fifty years later and is attributed to those who ruled after Trpimir. Gottshalk came to Trpimir court in 846 with an effort to find a safe place and protection, trying to save himself from the charges of heresy due to his teachings regarding predestination.7 It is highly unlikely that Gottshalk as educated man made such a mistake in appellation Trpimir in his writings. Most likely he remembered Trpimir as independent and strong ruler which offered him protection in the time of need, but knowing that formally he is not a king.

Few records imply Trpimir vagued wars in such way that he is not just a confident and pragmatic ruler but also competent warlord with tendency in winning every fight he started with opponents. Gottshalk mentions victory from 846 over people he refers to as Greeks. Most of the historians lean to except that Croatian duke got in conflict with some of Dalmatians municipals under the control of Byzantium or with some Byzantium expedition forces who tried to reclaim some lost positions in Dalmatians background exploiting weaknesses of Frankish Empire. Another possibility are Venetians, formally vassals of Byzantine (Greek) Emperor.8

Few records imply Trpimir vagued wars in such way that he is not just a confident and pragmatic ruler but also competent warlord with tendency in winning every fight he started with opponents. Gottshalk mentions victory from 846 over people he refers to as Greeks. Most of the historians lean to except that Croatian duke got in conflict with some of Dalmatians municipals under the control of Byzantium or with some Byzantium expedition forces who tried to reclaim some lost positions in Dalmatians background exploiting weaknesses of Frankish Empire. Another possibility are Venetians, formally vassals of Byzantine (Greek) Emperor.8

Other historical accounts suggest Trpimir managed to repel attack launched by Bulgarians in 852. under their ruler Mihajlo Boris, nation which is in that time conquered neighboring territories and countries, posing a treat to the Byzantium itself. After failed attempt toward Croatia, Bulgarians send envoys, peace negotiators to Croatian duke and in a name of their ruler exchanged gifts with representatives of Trpimir in the name of truth and mutual friendship. If we perceive Bulgaria as biggest military power on Balkan, equal relationship between members of two delegation seams astonishing and represent a huge diplomatic success for Trpimir. At Adriatic he fought against Saracens, stopping theme in plundering and kidnapping Christian ships.9

He had three, already mentioned sons, but after him Croatian throne went on to Domagoj, obviously a member of some other respected noble family which had had land properties likely positioned to some distance away from Klis, most likely around Knin.

Other articles from the series: “The Trpimirović Dynasty of Croatian Rulers”

- From the Arrival and Settling of Croats to Trpimir Ascending to the Throne

- The age of duke Trpimir

- Dukes Domagoj and Zdeslav

- Branimir and Muncimir

- The age of kings – Tomislav

- Church Councils and King Tomislav’s Heirs

- Stjepan Držislav

- The Heirs of Stjepan Držislav

- Petar Krešimir IV

- Demetrius Zvonimir

- Demetrius Zvonimir and Stephen II

- Trpimir acknowledged high power of Italic king and Frankish Emperor Lothar I., but he called himself “with Divine support duke of Croats“. It clearly shows that he wasn’t considered that he owes his power to Frankish emperor or king, but to God.

- In Gottshalks inscriptions Trpimir was mentioned as king of Slavs (Rex Sclavorum). The use of royal title for the Croatian ruler is likely to be found in other scripts and texts of the period some fifty years later. This shows us that Trpimir was ruler with royal reputation, for whom it wasn’t necessary to be crowned.

- Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb: Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada, 1994

- Ivo GOLDSTEIN, Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb: Novi Liber – Zavod za hrvatsku povijest FF-a, 1995

- Stjepan GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune starijoj hrvatskoj historiji, Book II, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1973

- Nada KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1971

- Vjekoslav KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata, Book I, Zagreb: Matica Hrvatska, 1972

- Tomislav RAUKAR, Hrvatsko srednjovjekovlje, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1997

- Tadija SMIČIKLAS, Poviest hrvatska, Book I, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1882

- Ferdo ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara, Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske, 1925

- 1 Vjekoslav KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata, Book I, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1972, page 76.

- 2 Nada KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u srednjem vijeku, Zagreb: Globus, 1990, page 60.

- 3 Stjepan GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune starijoj hrvatskoj historiji, Book II, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 197., page 141-167; Ivo GOLDSTEIN, Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb: Novi Liber – Zavod za hrvatsku povijest FF-a, 1995, page 202.

- 4 Tomislav RAUKAR, Hrvatsko srednjovjekovlje, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 199., page 28.

- 5 Ferdo ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara, Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske, 1925, page 330-331.

- 6 Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb: Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada, 1994, page 77-78.

- 7 God decides in which direction will human soul tend to- toward salvation or damnation, so good deeds in this world can’t save anybody from the fact his destiny is chosen for him – he is predetermined from the birth by predestination, more details in: Ivo GOLDSTEIN, Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb: Novi Liber – Zavod za hrvatsku povijest FF-a, 1995, page 201.

- 8 Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb: Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada, 1994, page 21.

- 9 Tadija SMIČIKLAS, Poviest hrvatska, Book I, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1882, page 183.

Your comment