In 879 Branimir, who was not related to Trpimirović dynasty, gets appointed to the throne.1 First plans of the new duke involved finding an ally who could guarantee him safety in the international relations. Regardless of whether he acclaimed the Italian king and Frankish emperor Charles the Fat (877-887), he couldn’t expect much from him. On the other side, there was Basil, who did not react after the murder of his protege because of his preoccupation with the conflicts in Syria and southern Italy. The best obvious solution was to ask the Pope for protection, because of his authority not only in the West, but also in Byzantium. Soon after, Branimir sends a letter to Rome, to the exceptionally politically active Pope John VIII, through John of Venice, a papal delegate who was traveling through Croatia on his way back from Moravia. In the letter, he expresses his and the loyalty of Croatian people to the apostolic throne of St. Peter. His example was followed by the first known Bishop of Nin, Theodosius. Having seen the letters, John VIII was delighted, so on 21st of May 879 on the feast of Ascension he proclaimed his blessing to duke Branimir, Croatian people and all of Croatian lands. He addressed by separate letters already on June 7 to both duke Branimir and bishop of Nin, expressing great joy because of their rejoining to the Holy Roman Church, and the day after he sent a letter to Bulgarian duke Michael Boris and to Dalmatian imperial cities expecting them to do the same.2 2 The Pope also fulfilled duke’s greatest plea – he confirmed his government, which was a public recognition of the authority of Croatian dukes.3 The political position of Croatia has thus been solved, but not the question of ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

In 879 Branimir, who was not related to Trpimirović dynasty, gets appointed to the throne.1 First plans of the new duke involved finding an ally who could guarantee him safety in the international relations. Regardless of whether he acclaimed the Italian king and Frankish emperor Charles the Fat (877-887), he couldn’t expect much from him. On the other side, there was Basil, who did not react after the murder of his protege because of his preoccupation with the conflicts in Syria and southern Italy. The best obvious solution was to ask the Pope for protection, because of his authority not only in the West, but also in Byzantium. Soon after, Branimir sends a letter to Rome, to the exceptionally politically active Pope John VIII, through John of Venice, a papal delegate who was traveling through Croatia on his way back from Moravia. In the letter, he expresses his and the loyalty of Croatian people to the apostolic throne of St. Peter. His example was followed by the first known Bishop of Nin, Theodosius. Having seen the letters, John VIII was delighted, so on 21st of May 879 on the feast of Ascension he proclaimed his blessing to duke Branimir, Croatian people and all of Croatian lands. He addressed by separate letters already on June 7 to both duke Branimir and bishop of Nin, expressing great joy because of their rejoining to the Holy Roman Church, and the day after he sent a letter to Bulgarian duke Michael Boris and to Dalmatian imperial cities expecting them to do the same.2 2 The Pope also fulfilled duke’s greatest plea – he confirmed his government, which was a public recognition of the authority of Croatian dukes.3 The political position of Croatia has thus been solved, but not the question of ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

Having liberated the country from the political dependency to Byzantine Empire, Branimir also cut off the link between the Diocese of Nin and the Patriarch of Constantinople.4 A chance of Church reforms emerged after the death of the Archbishop of Split, Martin, in 887. The Dalmatian clergy, despite the political changes in the country, remained faithful to the Patriarch of Constantinople, much like all of Dalmatia was still politically linked to the Empire. That way the Dalmatian dioceses have remained within their humble bounds opposed to the Diocese of Nin whose vast land was under the Pope’s legislative.5 Around 890 Theodosius, bishop of Nin, managed to become the Archbishop of Split. He was consecrated for Archbishop by the Patriarch of Aquileia Walbert, but not by the Pope Stephen V (885-891), who summoned him to come for the pallium in person.6 Knowing as a fact that at one moment the Croatian Bishop (episcopus Chroatorum) and the Archbishop of Split were the same person, we come to conclusion that gradually, but effectively, the ancient Trpimir’s endeavor to tighten Croatia’s bonds to the Byzantine Dalmatian cities had finally started to realize. Branimir was the first to have done this step through a non-violent way, but by using Christian universalism.7 The success was, however, short-lasting. Theodosius died shortly after, and Split and Nin were soon disunited once again. By the year of 892 Split had an archbishop by the name of Peter II, while his opponent Aldefred sat in Nin.8

Having liberated the country from the political dependency to Byzantine Empire, Branimir also cut off the link between the Diocese of Nin and the Patriarch of Constantinople.4 A chance of Church reforms emerged after the death of the Archbishop of Split, Martin, in 887. The Dalmatian clergy, despite the political changes in the country, remained faithful to the Patriarch of Constantinople, much like all of Dalmatia was still politically linked to the Empire. That way the Dalmatian dioceses have remained within their humble bounds opposed to the Diocese of Nin whose vast land was under the Pope’s legislative.5 Around 890 Theodosius, bishop of Nin, managed to become the Archbishop of Split. He was consecrated for Archbishop by the Patriarch of Aquileia Walbert, but not by the Pope Stephen V (885-891), who summoned him to come for the pallium in person.6 Knowing as a fact that at one moment the Croatian Bishop (episcopus Chroatorum) and the Archbishop of Split were the same person, we come to conclusion that gradually, but effectively, the ancient Trpimir’s endeavor to tighten Croatia’s bonds to the Byzantine Dalmatian cities had finally started to realize. Branimir was the first to have done this step through a non-violent way, but by using Christian universalism.7 The success was, however, short-lasting. Theodosius died shortly after, and Split and Nin were soon disunited once again. By the year of 892 Split had an archbishop by the name of Peter II, while his opponent Aldefred sat in Nin.8

At the same time as the process of christianization, a parallel process, ethnogenesis, accelerated rapidly during Branimir’s time. Along with the creation and strengthening of the Church organization, the logical order was the easier spread of the Croatian name among surrounding Slavic nations, and this is witnessed by the many discovered stone inscriptions, in various places from Nin in North-West to Muć north of Split. These are mostly fragments of altar septum’s of the Old Croatian churches.9 First such monument was found in Šopot near Benkovac, which states: BRANIMIRO COM[ES] … DUX CRUATORVM COGIT[AVIT]. This inscription also represents the first mention of the name Croat (Cruatorvm) in a stone tablet. The second inscription from Branimir’s time consists of seven fragments found in the walls of church of St. Michael in Nin. It also mentions its creator, abbot Teudebert, Frankish missionary, who was Branimir’s contemporary

At the same time as the process of christianization, a parallel process, ethnogenesis, accelerated rapidly during Branimir’s time. Along with the creation and strengthening of the Church organization, the logical order was the easier spread of the Croatian name among surrounding Slavic nations, and this is witnessed by the many discovered stone inscriptions, in various places from Nin in North-West to Muć north of Split. These are mostly fragments of altar septum’s of the Old Croatian churches.9 First such monument was found in Šopot near Benkovac, which states: BRANIMIRO COM[ES] … DUX CRUATORVM COGIT[AVIT]. This inscription also represents the first mention of the name Croat (Cruatorvm) in a stone tablet. The second inscription from Branimir’s time consists of seven fragments found in the walls of church of St. Michael in Nin. It also mentions its creator, abbot Teudebert, Frankish missionary, who was Branimir’s contemporary

The next inscription was found in Muć as a part of architrave of the altar septum. This inscription contains a year, 888, which makes it the first dated Croatian stone monument.10 The fourth inscription mentioning Branimir was found in Ždrapanj near Bribir. It’s contents are similar to the inscription from Nin, which is a dedication of prefect Pristina who refers to Branimir as the ruler of Slavs. The last, fifth, inscription was found in Otres, a village between Benkovac and Bribir, but only a fraction [ANNI] had been preserved of the supposed name.11 The use of Latin, language of the Bible, of Western liturgy, culture and science, in Croatian inscriptions containing names of rulers, is one of the key evidence of firm affiliation of the contemporary Croatia to the West European civilizational circle.12

The next inscription was found in Muć as a part of architrave of the altar septum. This inscription contains a year, 888, which makes it the first dated Croatian stone monument.10 The fourth inscription mentioning Branimir was found in Ždrapanj near Bribir. It’s contents are similar to the inscription from Nin, which is a dedication of prefect Pristina who refers to Branimir as the ruler of Slavs. The last, fifth, inscription was found in Otres, a village between Benkovac and Bribir, but only a fraction [ANNI] had been preserved of the supposed name.11 The use of Latin, language of the Bible, of Western liturgy, culture and science, in Croatian inscriptions containing names of rulers, is one of the key evidence of firm affiliation of the contemporary Croatia to the West European civilizational circle.12

Branimir had a wife Maruša of unknown ancestry with whom he once went on a pilgrimage to patriarchy of Aquileia, where their names were inscribed in the „Gospel of Cividale“, where Trpimir’s name had been also inscribed.13 His reign was marked by construction and restoration of churches, and Croatia has, thanks to him, reached the end of the 9th century as a strong and independent country.

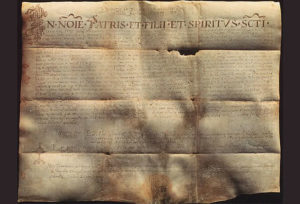

Muncimir, who succeeded Branimir in throne, came to power in 892. He was of Trpimirović descent, most probably the youngest son of Trpimir. He accentuates in his grant that he has come once again to his father’s throne.14 As he strived to keep good relations with the Church in Split, he once, following a conflict between the Aldefred, the Bishop of Nin, and Peter II, the Archbishop of Split, confirmed the same rights as Trpimir half a century earlier.15 Like Trpimir, he often spent time in Bijaće near Trogir. He and his wife, who is of unknown name and origin, both had a substantial court, similar to Frankish rulers.16 He constructed a church in Uzdolje, not far from Knin, and in a preserved inscription he is called princeps, which is a title until then unknown to Croatian rulers.17

Muncimir, who succeeded Branimir in throne, came to power in 892. He was of Trpimirović descent, most probably the youngest son of Trpimir. He accentuates in his grant that he has come once again to his father’s throne.14 As he strived to keep good relations with the Church in Split, he once, following a conflict between the Aldefred, the Bishop of Nin, and Peter II, the Archbishop of Split, confirmed the same rights as Trpimir half a century earlier.15 Like Trpimir, he often spent time in Bijaće near Trogir. He and his wife, who is of unknown name and origin, both had a substantial court, similar to Frankish rulers.16 He constructed a church in Uzdolje, not far from Knin, and in a preserved inscription he is called princeps, which is a title until then unknown to Croatian rulers.17  The Latin term princeps essentially means champion or ruler, but in medieval terminology it represented ruler honor greater than duke (dux), which is a solid proof of independence of Croatian rulers which was known of outside of Croatia.

The Latin term princeps essentially means champion or ruler, but in medieval terminology it represented ruler honor greater than duke (dux), which is a solid proof of independence of Croatian rulers which was known of outside of Croatia.

In Muncimir’s time, Croatia was strong enough to interfere in inner struggles in neighboring Serbia. Outcast Serbian aspirants found refuge in Croatian court, which was also the base for their military campaigns. Petar Gojniković, who was helped by Branimir in 891 to banish Prvoslav, Bran and Stefan, who were sons of Serbian duke Mutimir, were provided with no such support from Muncimir. In fact, Muncimir supported the banished brothers, offered them refuge and helped Bran in an attempt to return to power. Such aggressive foreign policy shows how mature and powerful Croatia became under Muncimir.

Thus, a stable and independant Croatia stepped into the 10th century, the century of kings.18

Other articles from the series: “The Trpimirović Dynasty of Croatian Rulers”

- From the Arrival and Settling of Croats to Trpimir Ascending to the Throne

- The age of duke Trpimir

- Dukes Domagoj and Zdeslav

- Branimir and Muncimir

- The age of kings – Tomislav

- Church Councils and King Tomislav’s Heirs

- Stjepan Držislav

- The Heirs of Stjepan Držislav

- Petar Krešimir IV

- Demetrius Zvonimir

- Demetrius Zvonimir and Stephen II

- During Branimir’s reign Croatia determined her own future within countries that belonged to Western Europe and by the decision of Pope John VIII Croatia was accepted as independent country of Christian West.

- Title of princeps appears in time of Branimir and continues during the reign of Muncimir. In medieval terminology this term signifies royal honor which was greater than honor of duke. This was a direct evidence of the growing independence of the Croatian rulers.

- Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb: Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada, 1994

- Ivo GOLDSTEIN, Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb: Novi Liber – Zavod za hrvatsku povijest FF-a, 1995

- Stjepan GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune starijoj hrvatskoj historiji, Book II, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1973

- Nada KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1971

- Lujo MARGETIĆ, Hrvatska država u doba narodnih vladara, Hrvatska i Crkva u srednjem vijeku: Pravnopovijesne i povijesne studije, Rijeka: Pravni fakultet Sveučilišta u Rijeci, 2000

- Tadija SMIČIKLAS, Poviest hrvatska, Book I, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1882

- Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII – XII. stoljeće): Rano doba hrvatske kulture, Book I, in: Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Hrvatska i Europa: kultura, znanost i umjetnost, Zagreb: Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1997

- Ferdo ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara, Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske, 1925

- Mate ZEKAN and others (ed.), Branimirova Hrvatska u pismima pape Ivana VIII., Second edition, Split: Književni krug, 1990

- 1 Nada KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u srednjem vijeku, , Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1971, 65; Mate ZEKAN and others (ed.), Branimirova Hrvatska u pismima pape Ivana VIII., Second Edition, Split: Književni krug, 1990, p. 9

- 2 Ferdo ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara, Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske, 1925, 377-380; Mate ZEKAN and others (ed.), Branimirova Hrvatska…, p. 45-71

- 3 Nada KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u srednjem vijeku…, 66; Mate ZEKAN and others (ed.), Branimirova Hrvatska…, 11-12; Lujo MARGETIĆ, Hrvatska država u doba narodnih vladara, in: Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII – XII. stoljeće): Rano doba hrvatske kulture, Book I, in: Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.) Hrvatska i Europa: kultura, znanost i umjetnost, Zagreb: Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1997, p. 203

- 4 Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb: Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada, 1994, p. 27

- 5 Dalmatian clergy turned to Pope only after Fotius’ schism, and the Dalmatian bishops were interested in the reestablishment of the former Church province of Salona, which would represent a realization of unity of the Church on both Croatian and Dalmatian territories. Stjepan GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune starijoj hrvatskoj historiji, Book II, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1973, 168-176; BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske…, p. 27

- 6 pallium, a liturgical mark wore by metropolitan archbishops, and it represents a special form of bond between the Metropolitan and the Pope. Ferdo ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara…, 391; Nada KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku…, p. 256

- 7 Lujo MARGETIĆ, Hrvatska država u doba narodnih vladara, in: Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII – XII. stoljeće), Rano doba hrvatske kulture, Book I, in: Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.) Hrvatska i Europa: kultura, znanost i umjetnost, Zagreb: Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1997, p. 203

- 8 Ferdo ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara…, 392; GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune…, Book II, from page 141

- 9 Ivo GOLDSTEIN, Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb: Novi Liber – Zavod za hrvatsku povijest FF-a, 1995, p. 262

- 10 Lujo MARGETIĆ, Hrvatska i Crkva u srednjem vijeku: Pravnopovijesne i povijesne studije, Rijeka: Pravni fakultet Sveučilišta u Rijeci, 2000, p. 227-249

- 11 Ivo GOLDSTEIN, Hrvatski rani srednji vijek…, p. 262-266

- 12 Mirjana MATIJEVIĆ-SOKOL, Latinski natpisi, in: Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII – XII. stoljeće)…, p. 242-243

- 13 Ferdo ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara…, p. 393

- 14 Tadija SMIČIKLAS, Poviest hrvatska, Book I, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1882, p. 196

- 15 Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske…, p. 29

- 16 Ferdo ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara…, p. 394

- 17 Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske…, p. 29

- 18 Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske…, p. 29

Your comment