Throughout Zvonimir’s reign, the Kingdom of Croatia preserved the strength it had during his predecessor, along with the capacity of leading a foreign policy. Thus, the changes in political relations on the Apennine peninsula have become a new opportunity for entanglement into a larger international conflict. Norman ruler Robert Guiscard made peace with the Pope in 1080 and, with his blessing, started with the preparations for a war with Byzantium. Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos (1081-1118) allied with Venice, who was not comfortable with the rise of Norman power on the Adriatic. Although sources are unclear regarding Normans’ allies, Robert was probably aided by Dubrovnik and upper Dalmatia, who then acknowledged him as their sovereign. It is most probable that Zvonimir, with his Croatian and Dalmatian people, as a papal vassal, participated in this war on the Normans’ side, because the reinstitution of Byzantine-Venetian domination on the Adriatic served neither him nor the Dalmatians. The war ended in 1085, with Robert’s death.

Throughout Zvonimir’s reign, the Kingdom of Croatia preserved the strength it had during his predecessor, along with the capacity of leading a foreign policy. Thus, the changes in political relations on the Apennine peninsula have become a new opportunity for entanglement into a larger international conflict. Norman ruler Robert Guiscard made peace with the Pope in 1080 and, with his blessing, started with the preparations for a war with Byzantium. Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos (1081-1118) allied with Venice, who was not comfortable with the rise of Norman power on the Adriatic. Although sources are unclear regarding Normans’ allies, Robert was probably aided by Dubrovnik and upper Dalmatia, who then acknowledged him as their sovereign. It is most probable that Zvonimir, with his Croatian and Dalmatian people, as a papal vassal, participated in this war on the Normans’ side, because the reinstitution of Byzantine-Venetian domination on the Adriatic served neither him nor the Dalmatians. The war ended in 1085, with Robert’s death.

Although heavily defeated, Venice gained the most from this war, as will the near future show. Namely, emperor Alexios granted Venice great merchant privileges in exchange for their assistance in the war, which have proven to be the ground for the later uprising Venetian economical power. An interesting fact is that Alexios gave to the new Venetian doge Vitale Faliero (1084-1096) jurisdiction over the Dalmatian theme, as an additional reward. This way the doge became a dux Dalmatiae, but at that point, it was a meaningless title, because there was nothing to confirm Venetian power in Dalmatia. Dalmatian cities were no longer connected to Byzantium which had proven so weak during the war that it had, at any moment, absolutely no chance of even getting close to these cities, let alone seize control over them.

During Zvonimir’s reign, much like during his predecessor’s, administrative system of the state further developed, and the layering of Croatian society, modeled on the western feudal systems, continued. The original sources speak of layering in the highest classes, thus mentioning titles such as: barons (barones), magnates (primates), dukes (comites), while the document issuers started referring to the old Croatian prefects as comes, in Latin.1

During Zvonimir’s reign, much like during his predecessor’s, administrative system of the state further developed, and the layering of Croatian society, modeled on the western feudal systems, continued. The original sources speak of layering in the highest classes, thus mentioning titles such as: barons (barones), magnates (primates), dukes (comites), while the document issuers started referring to the old Croatian prefects as comes, in Latin.1

King Demetrius Zvonimir was married to Helen the Beautiful, sister of Hungarian kings Geza and Ladislaus. He had a son named Radovan, who died before Zvonimir, and daughter Claudia, who married Vonika, a Croatian nobleman, who was of the patrician lineage Lapčan. At his daughter’s wedding, the king granted his son-in-law the estate of Karin, in hinterland of Zadar, which resulted in splitting of this patrician lineage into two branches –Lapčan and Karinjan.2

There are two theories on the death of this Croatian ruler. One of them states that he died of natural causes, however, the other theory, that also appears in the Croatian redaction of the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja, which is much more interesting, but also less probable, claims that Demetrius Zvonimir was killed by the „unfaithful Croats“. Being a brave soldier and a keen supporter of Christianity, inspired by the letter of the emperor and the pope, he decided two raise a great army and head out on a crusade to the Holy Land, but the disgruntled Croatian aristocracy gathered in a council on Kosovo field near Knin murdered him. This story is very doubtful considering that pope Urban II (1088-1099) didn’t announce the First Crusade until 1095, which was a few years after Zvonimir’s death. Be as it may, Demetrius Zvonimir died around 1089, and was buried inside the Knin cathedral.3

Croatia, as Neven Budak states, was unimpaired throughout Zvonimir’s reign. Zvonimir’s son Radovan died before his father, thus since Zvonimir was heirless, he was succeeded by the last Trpimirović descendant, Peter Krešimir IV’s nephew Stephen II. Having spent most of his life in the monastery of St. Stephen under Borovi in Split, after gaining power, he had nothing to relate to in order to restore his ancestors’ reputation. His government seemed to be reduced to narrow surroundings of Split, area which, as we already know, was always Trpimirović residence.

Croatia, as Neven Budak states, was unimpaired throughout Zvonimir’s reign. Zvonimir’s son Radovan died before his father, thus since Zvonimir was heirless, he was succeeded by the last Trpimirović descendant, Peter Krešimir IV’s nephew Stephen II. Having spent most of his life in the monastery of St. Stephen under Borovi in Split, after gaining power, he had nothing to relate to in order to restore his ancestors’ reputation. His government seemed to be reduced to narrow surroundings of Split, area which, as we already know, was always Trpimirović residence.

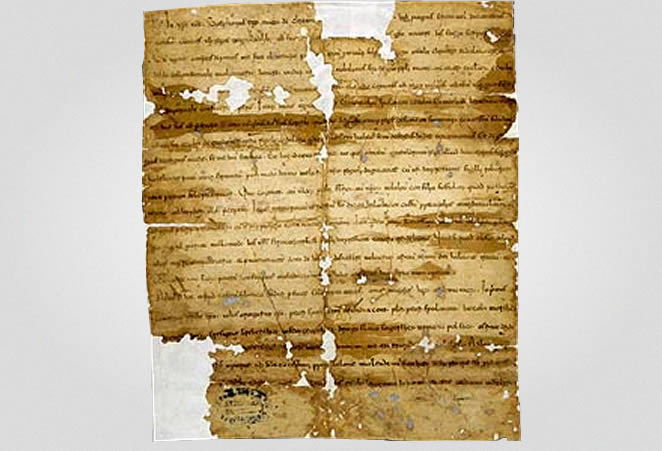

Territorial spread of his government is pointed out by the names of the prefects that accompanied him, and those were prefects of Primorje, Bribir, Cetina, Zagora, Poljice and Drid, who governed territory from the hinterland of Šibenik to Cetina. There is one document preserved from his time – a certificate of grant to Split Benedictines from the recently deceased king Zvonimir. It seems that Stephen was not capable of gathering the whole Kingdom around him and ruling in the old glory by the fact itself that he had no heir to guarantee the impecunious continuity of government.4 He died in 1091, and was buried in the crypt of Monastery of St. Stephen in Split, in the place where he spent most of his life. This marks the end of the story of Trpimirović dynasty, which has, with an exception of a few negligible intermissions, ruled the Croatian country and people for two and a half centuries.

Other articles from the series: “The Trpimirović Dynasty of Croatian Rulers”

- From the Arrival and Settling of Croats to Trpimir Ascending to the Throne

- The age of duke Trpimir

- Dukes Domagoj and Zdeslav

- Branimir and Muncimir

- The age of kings – Tomislav

- Church Councils and King Tomislav’s Heirs

- Stjepan Držislav

- The Heirs of Stjepan Držislav

- Petar Krešimir IV

- Demetrius Zvonimir

- Demetrius Zvonimir and Stephen II

- In the monastery of St. Gregory in Vrana, which Zvonimir granted to papal emissaries, there were two crowns of gold. It is assumed that these crowns belonged to Zvonimir’s predecessors, Tomislav and Stephen Držislav.

- Josip BRATULIĆ, Legenda o kralju Zvonimiru, e: Goldstein (ed.), Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski…, p. 235-240

- Ivo GOLDSTEIN (ed.), Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski, Zbornik radova znanstvenog skupa “Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski”, Zagreb: Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts – Croatian History Department, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Zagreb, 1997

- Ivo GOLDSTEIN, Kako, kada i zašto je nastala legenda o nasilnoj smrti kralja Zvonimira, Radovi Instituta za hrvatsku povijest 17 (1984), p. 35-52

- Stjepan GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune starijoj hrvatskoj historiji, vol. II-III, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1973-1975

- Vjekoslav KLAIĆ, Hrvatska plemena od XII. do XVI. stoljeća, Rad Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 130, Zagreb, 1897

- Vjekoslav KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata, vol. 1, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1972

- Vladimir KOŠĆAK, O smrti hrvatskog kralja Dmitra Zvonimira, e: Goldstein (ed.), Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski…, p. 223-228

- Tomislav RAUKAR, Prostor i društvo, e: Supičić (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće)…, p. 181-196

- Peter ROKAY, Motiv neostvarenog križarskog rata u biografijama srednjovjekovnih evropskih vladara, u: Goldstein (ur.), Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski…, p. 241-246

- Franjo SMILJANIĆ, Neke topografske dileme vezane uz vijesti o smrti kralja Zvonimira, u: Goldstein (ed.), Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski…, p. 229-233

- Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće): Rano doba hrvatske kulture, vol. I, e: same (ed.) Hrvatska i Europa: kultura, znanost i umjetnost, Zagreb: Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 1997

- 1 Vjekoslav KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata, vol. 1, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1972, p. 142; Tomislav RAUKAR, Prostor i društvo, in: SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće): Rano doba hrvatske kulture, vol. I, in: same (ed.) Hrvatska i Europa: kultura, znanost i umjetnost, Zagreb: Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 1997, p. 191

- 2 Vjekoslav KLAIĆ, Hrvatska plemena od XII. do XVI. stoljeća, Rad Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 130, Zagreb 1897, p. 17-18 and 61-62

- 3 GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune starijoj hrvatskoj historiji, vol. III, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1973, p. 169-215; Ivo GOLDSTEIN, Kako, kada i zašto je nastala legenda o nasilnoj smrti kralja Zvonimira, Radovi Instituta za hrvatsku povijest 17 (1984), p. 35-52; Vladimir KOŠĆAK, O smrti hrvatskog kralja Dmitra Zvonimira, in: GOLDSTEIN (ed.), Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski…, p. 223-227; Franjo SMILJANIĆ, Neke topografske dileme vezane uz vijesti o smrti kralja Zvonimira, in: same, p. 229-233; Josip BRATULIĆ, Legenda o kralju Zvonimiru, in: same, p. 235-240; Peter ROKAY, Motiv neostvarenog križarskog rata u biografijama srednjovjekovnih evropskih vladara, in: same, p. 241-246

- 4 GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune…, vol. III, p. 287-323; BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske…, p. 115-117

Your comment