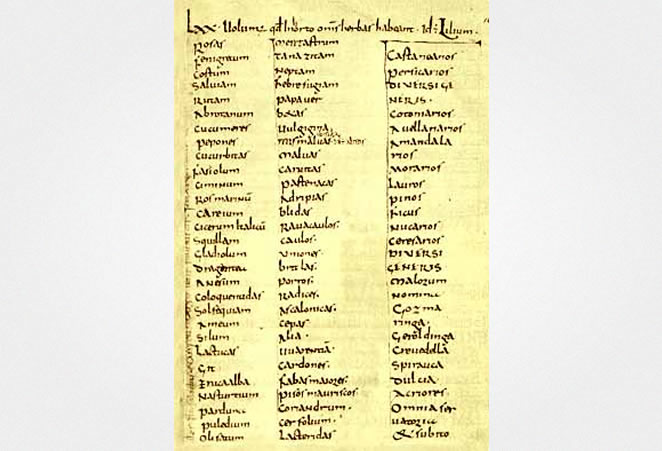

In the center of the Frankish state during the Carolingian government, the process of accession of small, free lands into large feudal estates was nearly entirely realized. Preserved sources tell us of an organization of large landowners, and by far the most important is Capitulare de villis that originated between 770 and 800. Under these regulations on guidance and management of royal estate reservations, both ecclesiastical and secular magnates governed the economical activity on their lands. Besides the Capitulare de villis, information regarding seigneur reservations exclusively exist in sources such as samples of church and public estates, the so called Brevium exempla made between 811 and 813 under the order of the royal government. In parallel to these sources, in Frankia we also find polyptychs, documents that contain an overview of financial status of rich priories. Apart from the information on their income, they also describe the life and work on the subordinate peasant particles. The most famous is the „Polyptych of the Abbey of Saint – Germain des Pres“ composed in 813 by the abbot Irmion. It contains a detailed description of each of the twenty five estates of that priory spread all across the central and northern France. Apart from the reservation land with all the components, cultures and buildings, it also states the subordinate peasant particles, the size of cultivated land within those particles, and describes the duties in kind of subordinate cultivators.

In the center of the Frankish state during the Carolingian government, the process of accession of small, free lands into large feudal estates was nearly entirely realized. Preserved sources tell us of an organization of large landowners, and by far the most important is Capitulare de villis that originated between 770 and 800. Under these regulations on guidance and management of royal estate reservations, both ecclesiastical and secular magnates governed the economical activity on their lands. Besides the Capitulare de villis, information regarding seigneur reservations exclusively exist in sources such as samples of church and public estates, the so called Brevium exempla made between 811 and 813 under the order of the royal government. In parallel to these sources, in Frankia we also find polyptychs, documents that contain an overview of financial status of rich priories. Apart from the information on their income, they also describe the life and work on the subordinate peasant particles. The most famous is the „Polyptych of the Abbey of Saint – Germain des Pres“ composed in 813 by the abbot Irmion. It contains a detailed description of each of the twenty five estates of that priory spread all across the central and northern France. Apart from the reservation land with all the components, cultures and buildings, it also states the subordinate peasant particles, the size of cultivated land within those particles, and describes the duties in kind of subordinate cultivators.

A unit of a large land of productional – organizational type during the Carolingian dynasty was an estate documented as a villa. The extent of such an estate varied between 200 and 2000 hectares, each of which was divided into two divisions:

- Landowner’s reservation land

- Subordinate cultivators’ particles1

Landowner’s reservation land is originally also known as terra indominicata or terra salica. In this land that the landowner kept for himself was the landowner’s court (curtis); an area enclosed by a wall in which there was a housing, and along with it were accommodations for the workers that lived and worked on the reservation land. Inside the walls there were an allotment and a vegetable garden, and outside the walls there was arable land of the landowner’s reservation that comprised of ploughs, meadows, vineyards and forrests. The composition of the reservation also included a church that was under the direct ownership and supervision of the owner of the villae. Besides the church itself, the owner also supervised its entire assets, and the land that was given to the church to support the priest that lived there. The reservation had its own mill which was rented out most of the time, and was used by the owner only on rare occasions. There was also a supervisor (villicus) on the estate, who was in charge of cultivation and exploitation of the reservation land, as well as the collection of duties in kind from the subordinate particles. Among the workers on a Carolingian period reservation there were also slaves, which were few due to the fact that they worked on the court as landowner’s service. They lived in special accommodations within the walls. They were known as prebendarii because they ate food from the landowner’s own supplies, and this is called prebenda. In some cases, the prebendarii had a separate small house outside the court’s walls, with an infield that was cultivated by the wife and children, while the head of the family was administering his duties in the landowner’s home.

Landowner’s reservation land is originally also known as terra indominicata or terra salica. In this land that the landowner kept for himself was the landowner’s court (curtis); an area enclosed by a wall in which there was a housing, and along with it were accommodations for the workers that lived and worked on the reservation land. Inside the walls there were an allotment and a vegetable garden, and outside the walls there was arable land of the landowner’s reservation that comprised of ploughs, meadows, vineyards and forrests. The composition of the reservation also included a church that was under the direct ownership and supervision of the owner of the villae. Besides the church itself, the owner also supervised its entire assets, and the land that was given to the church to support the priest that lived there. The reservation had its own mill which was rented out most of the time, and was used by the owner only on rare occasions. There was also a supervisor (villicus) on the estate, who was in charge of cultivation and exploitation of the reservation land, as well as the collection of duties in kind from the subordinate particles. Among the workers on a Carolingian period reservation there were also slaves, which were few due to the fact that they worked on the court as landowner’s service. They lived in special accommodations within the walls. They were known as prebendarii because they ate food from the landowner’s own supplies, and this is called prebenda. In some cases, the prebendarii had a separate small house outside the court’s walls, with an infield that was cultivated by the wife and children, while the head of the family was administering his duties in the landowner’s home.

An estate, apart from the reservation, also contained particles, and the main labour on the landowner’s reservation were subordinate peasants from those particles. A peasant particle from within the estate is referred to as mansus, comprised of a residential house with infield as a residence, and ploughs, meadows and vineyards. Eventhough they weren’t considered as a part of a mansus, forrests, pastures and hunting grounds were given to the use to particle holders free of charge or for special fees.

An estate, apart from the reservation, also contained particles, and the main labour on the landowner’s reservation were subordinate peasants from those particles. A peasant particle from within the estate is referred to as mansus, comprised of a residential house with infield as a residence, and ploughs, meadows and vineyards. Eventhough they weren’t considered as a part of a mansus, forrests, pastures and hunting grounds were given to the use to particle holders free of charge or for special fees.

Apart from a various number of mansi that went from a few up to a hundred, a villa could have also contained several different types of mansi, which were divided by the social – economical status and the origin of their holder, thus we distinguish:

- Mansi ingenuiles – meaning free mansi that were kept by the descendants of former members of free village counties that were forced to give their particle to a wealthier holder due to poverty, but kept cultivating it under the condition that they give the owner of that particle an installment in kind.

- Mansi serviles – particles that were held by former slaves that inhabited the particle of the landowner’s property.

- Mansi lidiles – a mansus category that was held by former germanic half-free men or liti. They most probably descend from the free Germans who became slaves as war prisoners, and were eventually, following the formation of large estates, given land from their masters, to cultivate, under the obligation to give duties in kind to their master.2

The differences between the mansus categories that were known even in the Antique, manifested through unequal obligations that mainly depended on the social status of the cultivator. Therefore, the servi cultivated their small particles by hand tools (hoe and shovel), whilst the colons cultivated their much larger particles using animal-drawn carts.

In the Carolingian time, the duties in kind were comprised of specific amounts of crops. Apart from the crops, these duties also included livestock (oxen, pigs and sheep). Widely spread was a duty of regular type that included a certain number of hens or other poultry off of each mansus, and along with each hen, it was also obligatory to include five or six eggs.

Along with the duties in kind, the transitional period introduced labour duties which related to end products, and these can be divided into two groups:

- Lumber products that the particle holders were obliged to provide in the form of firewood and boards that were used in different purposes; stable construction, vineyard poles, torches etc. These duties were regular and annual.

- Linen products (flax or wool) were duties in textile products, and they related to certain amounts of linen and cloth. Weaving was a commitment of all the servile mansi. It was performed by the women within the workshops inside the court.3

Working commitments covered obligations called servitium i. e. service, and they consisted of farming obligations which were the most difficult for the particle holder, and the most important for the landowner, manoperaea, works that related to the upkeep of fences, wells and buildings, underpass (carroperae and angarie) which meant delivery and shipping of raw materials and crops to and from the landowner’s court, that is, outside of the villae to a market or a harbour, and nights (noctes) which was so-called unpredictable work that was common in rich priories where there was a lack of manpower from time to time.

The differences between the obligations of ingenuile and servile mansi were obvious from both duties in kind and in labour. Whilst the duties in kind of ingenuile mansi understood the exact amount of crops from fields, a duty in wine, as well as hostilium and carnaticum, those of servile mansi referred to a certain amount of products of agricultural labour, which was defined by the supervisor of the estate, depending on the fruitfulness of harvest and the number of smal livestock of the cultivator. The working commitments of ingenuile and servile mansi differed by the fact that the first ones included plough cultivation, manoperae, carroperae, angariae and noctes, whilst the latter ones were much more demanding, and included availability for all kinds of duties three days every week. Beside that, every servile mansus had to perform an additional working obligation during the seasonal agricultural work in the reservation, which was usually a form of night watch on curtis, herding of pigs and sheep, and supplying the court with wood and beer.

The differences between the obligations of ingenuile and servile mansi were obvious from both duties in kind and in labour. Whilst the duties in kind of ingenuile mansi understood the exact amount of crops from fields, a duty in wine, as well as hostilium and carnaticum, those of servile mansi referred to a certain amount of products of agricultural labour, which was defined by the supervisor of the estate, depending on the fruitfulness of harvest and the number of smal livestock of the cultivator. The working commitments of ingenuile and servile mansi differed by the fact that the first ones included plough cultivation, manoperae, carroperae, angariae and noctes, whilst the latter ones were much more demanding, and included availability for all kinds of duties three days every week. Beside that, every servile mansus had to perform an additional working obligation during the seasonal agricultural work in the reservation, which was usually a form of night watch on curtis, herding of pigs and sheep, and supplying the court with wood and beer.

The second half of the 9th century introduces a process of mansus specialization. Artisans such as blacksmiths, shoemakers, canters and goldsmiths had particles of their own, which they cultivated, but were free of any duties in kind or in labour. In turn, they were obliged to deliver a certain amount of their product to the court each year. The similar practice was applied on work supervisors, rangers and accountants. They had an ingenuile mansus each, from which they didn’t give any sort of duties other than providing their service.

Related articles:

- As a result of population growth, there is not one but even more than three peasant families living in a single mansus in the first half of the 9th century. All of those families were direct cultivators of the landowner’s property.

- Miroslav BRANDT, Srednjovjekovno doba povijesnog razvitka, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1995

- Joseph CALMETTE, Feudalno društvo, Sarajevo: Veselin Masleša, 1964

- 1 Miroslav BRANDT, Srednjovjekovno doba povijesnog razvitka, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1995, p. 194

- 2 Miroslav BRANDT, Srednjovjekovno doba povijesnog razvitka, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1995, p. 195

- 3 Miroslav BRANDT, Srednjovjekovno doba povijesnog razvitka, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1995, p. 198

Your comment