Peter Krešimir IV came to power in 1058. Even though there is no preserved monument to enable determining the date and location of his coronation, there is no doubt that he was in fact a king. His residence was Biograd, where the royal court was located at the time.1 The image of Peter Krešimir IV was probably preserved in the mysterious tablet inside the Split baptistery, that displays an XIth century Croatian ruler sitting on the throne with a crown and a cross.2

Peter Krešimir IV came to power in 1058. Even though there is no preserved monument to enable determining the date and location of his coronation, there is no doubt that he was in fact a king. His residence was Biograd, where the royal court was located at the time.1 The image of Peter Krešimir IV was probably preserved in the mysterious tablet inside the Split baptistery, that displays an XIth century Croatian ruler sitting on the throne with a crown and a cross.2

Following his ascension, the new Croatian king faced a schism that happened in 1054. After the Lateran council of 1059, in which all the requests placed to that date with the clergy subject to the Pope were adopted, the Church started with the organization of a similar Synod in order to spread the newly adopted rules outside Rome. Thus, in 1060 pope Nicholas II (1058-1061) sent his emissary Meinhard to Croatia, who, among other things, held a church council in Split. The main issue of this church council were the practices in Dalmatian-Croatian Church, which followed the traditions of the Christian East, in particular priests being allowed to marry.

However, the worst consequences for Croatian clergy brought the decisions against the practice of Slavenic liturgy. Although popes were never clear on whether ecclesiastical teachings in books written in Slavenic language were righteous or heretic, 11th century and concurrent reform movement compared to the previous, 10th century, was marked by a strict policy of the Church, because it was considered that such distinct dissimilarities might seriously threaten the unity of the western Christianity, especially in parts that were politically and traditionally tied to Byzantium. Thus the decision was made that all the churches that served liturgy in Slavenic language were to be closed, and all the priest candidates were forced to learn Latin henceforward. The council also appointed Osor bishop Lovro as the Split archbishop, instead of Ivan, and that decision was confirmed by the Pope himself, who sent him pallium over his legate.3 This bishop was the most notable supporter of the reform movement in Croatia, whose party outweighed, and it was without a doubt supported by Krešimir himself.4 The king also stimulated the founding of two Benedictine monasteries in his capital, Biograd, one of which, the monastery of St. John, was, at the time, the richest abbey in Croatia. Another monastery, St. Peter’s in Draga on Rab, was founded by his permission, and the Benedictine nunnery of St. Mary in Zadar was released of all taxes.5

However, the worst consequences for Croatian clergy brought the decisions against the practice of Slavenic liturgy. Although popes were never clear on whether ecclesiastical teachings in books written in Slavenic language were righteous or heretic, 11th century and concurrent reform movement compared to the previous, 10th century, was marked by a strict policy of the Church, because it was considered that such distinct dissimilarities might seriously threaten the unity of the western Christianity, especially in parts that were politically and traditionally tied to Byzantium. Thus the decision was made that all the churches that served liturgy in Slavenic language were to be closed, and all the priest candidates were forced to learn Latin henceforward. The council also appointed Osor bishop Lovro as the Split archbishop, instead of Ivan, and that decision was confirmed by the Pope himself, who sent him pallium over his legate.3 This bishop was the most notable supporter of the reform movement in Croatia, whose party outweighed, and it was without a doubt supported by Krešimir himself.4 The king also stimulated the founding of two Benedictine monasteries in his capital, Biograd, one of which, the monastery of St. John, was, at the time, the richest abbey in Croatia. Another monastery, St. Peter’s in Draga on Rab, was founded by his permission, and the Benedictine nunnery of St. Mary in Zadar was released of all taxes.5

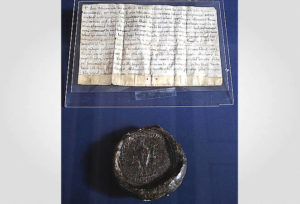

Through Church, which he supported and aided, Krešimir built a connection to transfer his government to Dalmatia. The province still acknowledged formal authority of the eastern emperor, but the crisis in the Empire lasted already for several years, so the central government in Dalmatia relied on catepans, but basically every city was responsible of its own destiny. Byzantium was then in constant threat from the East by Turks, and from the Mediterranean by Normans, thus it was inevitable that Dalmatia finally falls once more under the legislative of the Croatian king, which happened in 1069 when Krešimir’s escort is accompanied by catepan Lav. Krešimir was thoroughly involved regarding the issue of Dalmatia, in comparison to his predecessors, so he spoke, with full right, of the Adriatic coast as „our Adriatic sea“. By this grand diplomatic achievement, Krešimir succeeded in accomplishing Croatia’s hundred year long aspiration to unite with the ancient cultural centers of the eastern Adriatic. From then onward, the term Regnum Dalmatiae et Chroatiae marked a unique political, administrative and internationally recognized territory, and the king obliged himself to respect the freedom and ancient rights of each city.6 The successes that led to expansion of Croatian territory made Krešimir to grant the island of Maon to the monastery of St. Chrysogonus, and to state on the grant certificate that, by the help of God, he managed to stretch our borders on land and at „our sea“.7

Through Church, which he supported and aided, Krešimir built a connection to transfer his government to Dalmatia. The province still acknowledged formal authority of the eastern emperor, but the crisis in the Empire lasted already for several years, so the central government in Dalmatia relied on catepans, but basically every city was responsible of its own destiny. Byzantium was then in constant threat from the East by Turks, and from the Mediterranean by Normans, thus it was inevitable that Dalmatia finally falls once more under the legislative of the Croatian king, which happened in 1069 when Krešimir’s escort is accompanied by catepan Lav. Krešimir was thoroughly involved regarding the issue of Dalmatia, in comparison to his predecessors, so he spoke, with full right, of the Adriatic coast as „our Adriatic sea“. By this grand diplomatic achievement, Krešimir succeeded in accomplishing Croatia’s hundred year long aspiration to unite with the ancient cultural centers of the eastern Adriatic. From then onward, the term Regnum Dalmatiae et Chroatiae marked a unique political, administrative and internationally recognized territory, and the king obliged himself to respect the freedom and ancient rights of each city.6 The successes that led to expansion of Croatian territory made Krešimir to grant the island of Maon to the monastery of St. Chrysogonus, and to state on the grant certificate that, by the help of God, he managed to stretch our borders on land and at „our sea“.7

The government has also been strengthening in central Croatia, as well as in the North. There are, for the first time ever, two bans in the king’s escort, Gojčo and Zvonimir. The stability of the country led to a more active external policy in the eastern part of hinterland. When a rebellion against Byzantium outbroke in the area of Skopje, the leader of the rebellion, a local nobleman Georgije Vojtjeh, allied not only with the ruler of Duklja Mihajlo Bodin, but also with some Croatians. However, the rebellion failed in 1073, along with the ambitions of the Croatian king. In time of the rebellion, the duchy of Neretva and Bosna were most probably in Croatian possession, which made possible the direct cooperation of Krešimir with Mihajlo and Georgije.

Zvonimir strengthened his position in the Kingdom after a successful conflict against the Istrian margrave Ulrich I Weimar-Orlamünde (1069-1070) on western (Istrian) borders and thus most likely intruded himself as Krešimir’s heir.8 Soon after, he was rewarded the title of duke, which was until then carried by Krešimir’s nephew Stephen, who will, for medical or political reasons, be placed in a Split monastery of St. Stephen, and wait for the end of Zvonimir’s reign so he could himself sit on the throne.9

Zvonimir strengthened his position in the Kingdom after a successful conflict against the Istrian margrave Ulrich I Weimar-Orlamünde (1069-1070) on western (Istrian) borders and thus most likely intruded himself as Krešimir’s heir.8 Soon after, he was rewarded the title of duke, which was until then carried by Krešimir’s nephew Stephen, who will, for medical or political reasons, be placed in a Split monastery of St. Stephen, and wait for the end of Zvonimir’s reign so he could himself sit on the throne.9

Although historians’ opinions on the events that followed king Peter Krešimir IV’s death are divided, the most probable thesis is that his heir was Zvonimir, and not Slavac. The chronological problem was solved by Miho Barada by placing Slavac in the last decade of 11th century.10

The famous Croatian ruler, Peter Krešimir IV, spread the borders more than any Croatian ruler before him; Croatia stretched from Drava to Neretva, and from the sea to Drina.11 After Krešimir disappeared from the political scene, a papal emissary Gerard came to Croatia in 1075 to preside a church council in Split. The council resulted in restoration of the diocese in Nin, but the main purpose of this convocation was to consolidate ecclesiastical reforms.

Other articles from the series: “The Trpimirović Dynasty of Croatian Rulers”

- From the Arrival and Settling of Croats to Trpimir Ascending to the Throne

- The age of duke Trpimir

- Dukes Domagoj and Zdeslav

- Branimir and Muncimir

- The age of kings – Tomislav

- Church Councils and King Tomislav’s Heirs

- Stjepan Držislav

- The Heirs of Stjepan Držislav

- Petar Krešimir IV

- Demetrius Zvonimir

- Demetrius Zvonimir and Stephen II

- Peter Krešimir IV was suspected of murdering his brother Gojislav, but was released from charges after twelve of his prefects swore of his innocence in front of pope’s emissary.

- Amiko, Norman duke of Giovinazzo in Apulia imprisoned Peter Krešimir in 1074 near Caska on the Isle of Pag, which led to a settlement by which Split, Trogir, Zadar, Biograd and Nin were briefly handed over to Normans, until they were banished by the Venetians.

- Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb: Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada, 1994.

- Igor FISKOVIĆ, Reljef kralja Petra Krešimira IV., Split: Muzej hrvatskih arheoloških spomenika, 2002.

- Stjepan GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune, vol II, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1973 – 1975.

- Lujo MARGETIĆ, Hrvatska država u doba narodnih vladara, ed: Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće): Rano doba hrvatske kulture, vol. I, ed: same (ed.) Hrvatska i Europa: kultura, znanost i umjetnost, Zagreb: Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1997.

- Marija MOGOROVIĆ CRLJENKO, Istarski markgrofovi iz obitelji Weimar Orlamünde u konstelaciji odnosa Carstva i papinstva u doba borbe za investituru, Godišnjak Njemačke narodne zajednice – VDG Jahrbuch 10, 2003.

- Tadija SMIČIKLAS, Poviest hrvatska, vol. one, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1882.

- Franjo ŠANJEK, Crkva i kršćanstvo u Hrvata: Srednji vijek, Zagreb: Kršćanska sadašnjost, 1993.

- Ferdo ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara, Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske, 1925.

- 1 Ferdo ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara, Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske, 1925, p. 499-500

- 2 Igor FISKOVIĆ, Reljef kralja Petra Krešimira IV., Split: Muzej hrvatskih arheoloških spomenika, 2002

- 3 ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara…, p. 508

- 4 At that period, glagolitic alphabet turned from liturgical to diplomatic script, thus no reform could prevent it from being used. In such a complicated situation, the king sought support in the reform Church, predicting its victory.

- 5 Franjo ŠANJEK, Crkva i kršćanstvo u Hrvata: Srednji vijek, Zagreb: Kršćanska sadašnjost, 1993, p. 68-72; Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada, 1994, p. 41-42

- 6 ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara…, p. 523-524; Lujo MARGETIĆ, Hrvatska država u doba narodnih vladara, ed: Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće), Rano doba hrvatske kulture, vol. I, ed: same (ed.) Hrvatska i Europa: Kultura, znanost i umjetnost, Zagreb: Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1997, p. 205-206

- 7 Tadija SMIČIKLAS, Poviest hrvatska, book one, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1882, p. 249; Stjepan GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune, vol. II, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1973, p. 417-435

- 8 Marija MOGOROVIĆ CRLJENKO, Istarski markgrofovi iz obitelji Weimar Orlamünde u konstelaciji odnosa Carstva i papinstva u doba borbe za investituru, Godišnjak Njemačke narodnosne zajednice – VDG Jahrbuch 10 (2003), p. 83-89

- 9 BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske…, p. 44

- 10 BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske…, p. 44

- 11 ŠIŠIĆ, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara…, p. 536

where exactly in Sibenik is this monument of Petar Kresimir, Im going there and cant seem to find it on the map?

thank you !

Perivoj Roberta Visanija – https://goo.gl/maps/Dfv8UWNssmADxPt97