The tradition of bronze door craftsmanship dates back all the way to ancient times. One of the rare samples from the Ancient Rome are massive bronze doors on Pantheon in Rome, dating back to 125 AD. During the late Antique period bronze doors were installed on the Early Christian basilica of Santa Sabina in Rome and the church of Sant’ Ambrogio in Milan.

In the succeeding period, bronze doors are crafted mostly in Byzantium, some of which are imported in the West (a large number is preserved in Italy). Subsequently, this triggered a tradition of bronze door craftsmanship across Italy (i.e. Verona, Benevento, Monreale and Pisa) during XIth and XIIth century.1

Earlier bronze doors were crafted as decorational or flat plates with an engraved amblem, monogram, cross, or some other display, and set up on a wooden kernel afterward. The novelty are the doors from Hildesheim (originally on the church of St. Michael, today on the cathedral in same town), molten in a single piece, using the lost wax method, also featuring a figural decoration.

Bronze

Bronze is an alloy of copper with zinc or tin, at a ratio that varies depending on the period, the region, or even the workshop where the work was crafted.2 Alloys with more tin or zinc are a lot more fluid in liquid state, so it enables achieving the finest details when pouring into a mold. It is the favorite of most craftsmen because it’s very simple to process, and yet very solid and resistant to weather conditions.

Cast bronze can be decorated by techniques of engraving, investment, enamelling, gilt… When used for door manufacturing, bronze plates or separate groups of panels can be secured with a wooden framework, allowing the doors to be cast as a whole, or in one piece.

The lost wax method

In the middle ages, the usual process when crafting sculptures of bronze was a procedure known as cire perdue, or the „lost wax method“. The first step was to create the sculpture out of wax, which would than be overspread by clay or gypsum. By heating the mold, the wax melted leaving a cavity which would than be filled with liquid metal. Afterwards, the cast was layed in sand, so it would not break. This was very unpredictable and potentially expensive process, because the errors could have only been amended by rebuilding the wax model.3 This procedure is mentioned in an inscription on a lion-head shaped bronze handle on a cathedral in Trier, saying: „What the wax made, fire took away, and the bronze revealed.“4

The Italian door group

In the XIth century, in Italy, there were six bronze doors. All of them were crafted either in Byzantium or modeled on the Byzantine. Margaret English Frazer, in her article „Church Doors and the Gates of Paradise: Byzantine Bronze Doors in Italy“, in which she writes about bronze doors in Italy in XIth and XIIth century, says that Italians crafted doors modeled on the Byzantine style that symbolized the Gates of Heaven. Taken in consideration all of the samples, they can be divided into four groups, by the „paths“ that they hoped to reach and open the Gates of Heaven. This can happen through intercession of Virgin Mary and the saints to the Christ (Amalfi, Atrani, Venice), apostolic example (Rome), guidance of the archangels (Monte Sant’Angelo), or a new birth in Christ through baptism (Salerno).5

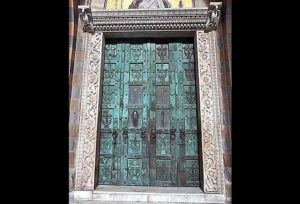

Amalfi, Cathedral of St. Andrew

Bronze doors from the Cathedral of St. Andrew in Amalfi, dating roughly from 1060, consist of twenty-four rectangular fields. The central four are decorated with the inset silver figures of Christ, Virgin Mary, St. Andrew and St. Peter. Other twenty fields are displaying leaved crosses. The Virgin Mary is placed left of the Christ, with hands raised in prayer. She leads prayers of St. Andrew and St. Peter for the souls of all who enter the church. Margareth English Frazer links the displayed characters with the leaved crosses. She claims that the success of Virgin Mary and saints’ prayers depends on Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, which opened a path to human salvation. The crucifix on the door is symbolically presented by a leaved cross. It resembles the tree of life – an instrument of human salvation. Finally, she concludes that the leaved crosses appear on many Byzantine doors, on the relics of the true cross, sarcophagi…6

Bronze doors from the Cathedral of St. Andrew in Amalfi, dating roughly from 1060, consist of twenty-four rectangular fields. The central four are decorated with the inset silver figures of Christ, Virgin Mary, St. Andrew and St. Peter. Other twenty fields are displaying leaved crosses. The Virgin Mary is placed left of the Christ, with hands raised in prayer. She leads prayers of St. Andrew and St. Peter for the souls of all who enter the church. Margareth English Frazer links the displayed characters with the leaved crosses. She claims that the success of Virgin Mary and saints’ prayers depends on Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, which opened a path to human salvation. The crucifix on the door is symbolically presented by a leaved cross. It resembles the tree of life – an instrument of human salvation. Finally, she concludes that the leaved crosses appear on many Byzantine doors, on the relics of the true cross, sarcophagi…6

The doors were donated to the church by a wealthy merchant Pantaleone from Amalfi who lived in Constantinople. He was a very success businessman who traded with his father between Amalfi and Constantinople. Beside these, he has donated several other doors to Italian churches, which will be discussed later in this article. He dedicated them to his saint and protector for forgiveness of his sins, and salvation of his soul. The doors were crafted in Constantinople by the craftsman Symon of Syria.

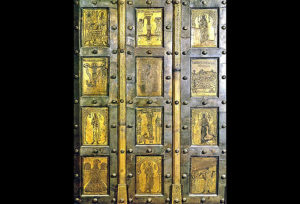

Venice, Basilica of St. Mark

The south portal on the basilica of St. Mark also has bronze doors that belong to the discussed period. They were formerly called the portal of St. Clement. The doors were built in Constantinople around 1080 for an unknown donor.7 They consist of 28 panels in each of which there is a figure, including Christ, Virgin Mary, the saints, two crosses on a base of three steps under arcs, and four decorative animal and herbal motifs. Nowadays, the panels are mixed up, and are not in the same order as they were in the original. Nevertheless, when the Virgin Mary and Christ are placed at the top of the doors, between the two crosses, and the saints line up by church hierarchy, we get the order of Byzantine hierarchy – with three rows of apostles, one row of patriarchs, and, finally, a row of saints – warriors.8

The door in Amalfi, Atrani and Venice show subjects that represent entrance to holy grounds. Their decoration displaying mediation of the Virgin Mary and saints, is connected to the same ones on the portals of churches and sanctuaries in Constantinople.

Rome, San Paolo fuori le mura

The bronze doors were donated to the church by Pantaleone from Amalfi in 1070, who dedicated it to St. Paul, in order to be granted opening the doors to eternal life. The iconography is concentrated on St. Paul’s teachings of Christ’s transformation and resurrection, for it will lead Pantaleone to the Gates of Heaven.9 It shows a different decoration scheme of Italian doors, based on the example and council of the apostles. The doors are divided into four parts, each of which consists of twelve panels that are decorated with insets made of silver and patina. It displays the following themes: twelve feasts from Annunciation to Descent of the Holy Spirit, twelve prophets holding scrolls with their prophecies, twelve apostles (panel with St. Paul includes the figures of Christ and St. Pantaleone), and twelve scenes of death and martyrdom of apostles. There are additional panels on the doors, two with leaved crosses, two depicting eagles, and two containing inscriptions.

The bronze doors were donated to the church by Pantaleone from Amalfi in 1070, who dedicated it to St. Paul, in order to be granted opening the doors to eternal life. The iconography is concentrated on St. Paul’s teachings of Christ’s transformation and resurrection, for it will lead Pantaleone to the Gates of Heaven.9 It shows a different decoration scheme of Italian doors, based on the example and council of the apostles. The doors are divided into four parts, each of which consists of twelve panels that are decorated with insets made of silver and patina. It displays the following themes: twelve feasts from Annunciation to Descent of the Holy Spirit, twelve prophets holding scrolls with their prophecies, twelve apostles (panel with St. Paul includes the figures of Christ and St. Pantaleone), and twelve scenes of death and martyrdom of apostles. There are additional panels on the doors, two with leaved crosses, two depicting eagles, and two containing inscriptions.

The doors decorated with the cycle of feasts are not without a model in Byzantium – during the middle Byzantine period, the scenes from the life of Christ, oft in the numbers of twelve, were linked to various parts of the liturgy. They were pictured on iconostasis, revealing the connection between decorations on doors and iconostasis.10

Monte Sant’Angelo, Monte Gargano

These doors display the third iconographic plan to enter the Heaven. They were crafted in Constantinople in 1076, probably for the same Pantaleone who donated doors to the cathedral in Amalfi. He appositely dedicated the doors to the archangel Michael, since they are posted on the entrance to his most significant pilgrimage site in Western Europe. The doors are divided to twenty-four fields, twenty-three of which display angelic artworks from the Old and the New Testament, and the last one having inscribed a votive inscription. The left wing of the doors displays events before the birth of Christ, starting with casting the Devil out of Heaven, and finishing with the Annunciation to Zachariah. On the right wing are Michael’s deeds after the birth of Christ, including three local miracles: Michael’s apparition to Lawrence, the Bishop of Siponto (regarding the fact that St. Lawrence was buried here), aiding St. Martin of Tours in destroying the pagan temple, and the crowning of St. Cecilia and St. Valerian. Regardless of the prototype, the doors in Monte Sant’Angelo lead pilgrims into sanctuary with a message of salvation: a Christian, who will be guided by the faith of hereby displayed saints, shall be guided by archangel Michael through upheavals of earthly life, which will finally lead him to Heaven.11

These doors display the third iconographic plan to enter the Heaven. They were crafted in Constantinople in 1076, probably for the same Pantaleone who donated doors to the cathedral in Amalfi. He appositely dedicated the doors to the archangel Michael, since they are posted on the entrance to his most significant pilgrimage site in Western Europe. The doors are divided to twenty-four fields, twenty-three of which display angelic artworks from the Old and the New Testament, and the last one having inscribed a votive inscription. The left wing of the doors displays events before the birth of Christ, starting with casting the Devil out of Heaven, and finishing with the Annunciation to Zachariah. On the right wing are Michael’s deeds after the birth of Christ, including three local miracles: Michael’s apparition to Lawrence, the Bishop of Siponto (regarding the fact that St. Lawrence was buried here), aiding St. Martin of Tours in destroying the pagan temple, and the crowning of St. Cecilia and St. Valerian. Regardless of the prototype, the doors in Monte Sant’Angelo lead pilgrims into sanctuary with a message of salvation: a Christian, who will be guided by the faith of hereby displayed saints, shall be guided by archangel Michael through upheavals of earthly life, which will finally lead him to Heaven.11

Byzantine and Italo-Byzantine doors in Italy show the believers various paths to Heaven: through intercession of Virgin Mary and the saints, the counsel of apostles, the guidance of the archangels (Monte Sant’Angelo), and the new birth in Christ through baptism. Each of them shows the prior Christ’s sacrifice, which was simbolically displayed by the crosses on the doors. One can reach Heaven only through Christ, because He is the gates of Heaven:

“I am the gate;

whoever enters through me will be saved.

He will come in and go out

and find pasture”.(John 10, 9)12

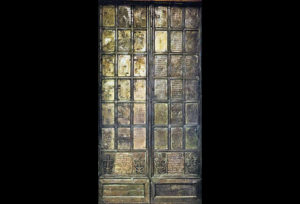

Monte Cassino

The doors in Monte Cassino consist of forty-two fields. In the lowest row there are two votive inscriptions, flanked with leaved crosses. Upon them is an inscription of the name of the donor, Maurus Amalfi, along with 1066 – the year of its creation. Above these, there are thirty-six other fields (eighteen on each side) on which is a list of monastic estates.

The crafting of these doors is documented in the work „Chronica monasterii Casinensis“ by Leon from Ostia, the monastery’s archivist and librarian at the time of abbot Desiderius (1058-1087, from 1086 pope Victor III) and his successor Oderisius I. Leon writes that after 1065 Desiderius’ trip to Amalfi, he liked the bronze doors on their cathedral, which were built in Constantinople, so much that he decided to order one for his abbey, from this city.13 This text does not mention the name of the donor Maurus (father of Pantaleone, the donor of the doors for the cathedral in Amalfi), unlike the inscription on the doors.

Although the doors in Monte Cassino were some wise modeled on the ones in Amalfi, the comparison shows they have almost nothing in common. Exception are only the leaved crosses which appear on both doors.

Today, the doors are not preserved in its original form. Twenty out of thirty-six original panels originate from a radical reconstruction done at the time of abbot Oderisius II. (1123-1126). On these fields the letters are filled with silver insets. The remaining sixteen fields are slightly smaller, and their letters have no filling. Herbert Bloch in his article „Origin and Fate of the Bronze Doors of Abbot Desiderius of Monte Cassino“ tends to prove that these fields were originally part of the side doors that led to naves of the basilica. He reckons that these fields might have been crafted somewhat later, but probably still date from Oderisius’ time. An earlier theory explains that, after the earthquake in 1349, some lost panel might have been replaced. H. Block finds this theory unacceptable.

Today, the doors are not preserved in its original form. Twenty out of thirty-six original panels originate from a radical reconstruction done at the time of abbot Oderisius II. (1123-1126). On these fields the letters are filled with silver insets. The remaining sixteen fields are slightly smaller, and their letters have no filling. Herbert Bloch in his article „Origin and Fate of the Bronze Doors of Abbot Desiderius of Monte Cassino“ tends to prove that these fields were originally part of the side doors that led to naves of the basilica. He reckons that these fields might have been crafted somewhat later, but probably still date from Oderisius’ time. An earlier theory explains that, after the earthquake in 1349, some lost panel might have been replaced. H. Block finds this theory unacceptable.

After the doors were damaged in World War II, it was discovered that some fields have figures of apostles on their back sides. Most authors14 believe these were a part of Desiderius’ doors from Constantinople.

The doors from Monte Cassino suffered a lot of damage as the centuries passed, first when the panels were turned and printed between 1123 and 1126, then again in the earthquake in 1349, and during the decades of storage, and finally during the bombings in 1944.15

Examples of bronze doors in North Europe

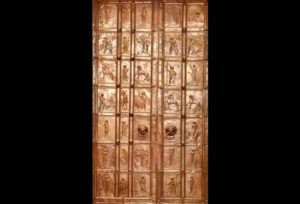

Hildesheim, Church of St. Michael

The church of St. Michael in Hildesheim began construction in 1001, the crypt was sanctified in 1015, and it is considered that the bronze doors were built the same year, which were primarily posted on the main entrance to the church, and stand today on the cathedral in the same town.16

The Hildesheim bronze doors are one of the most famous and most important bronze doors of this period. They were ordered by archbishop Bernward from Hildesheim, who was a tutor of Otto III, and the chaplain of the imperial court, on behalf of the church of St. Michael. Bernward was an assistant to the deacon during the construction of the great Willigis’ cathedral. He was the bishop of Hildesheim from 993 to 1022. Some German historians of art believe that Willigis’ church (978 to 1009) served as a model for the church of St. Michael.17

The Hildesheim bronze doors are one of the most famous and most important bronze doors of this period. They were ordered by archbishop Bernward from Hildesheim, who was a tutor of Otto III, and the chaplain of the imperial court, on behalf of the church of St. Michael. Bernward was an assistant to the deacon during the construction of the great Willigis’ cathedral. He was the bishop of Hildesheim from 993 to 1022. Some German historians of art believe that Willigis’ church (978 to 1009) served as a model for the church of St. Michael.17

They were the first decorated bronze doors cast in one piece, in all the West, since the Roman time.18 Here we can notice some renewed tendencies of artists toward figural sculpture in northern art. The previous bronze doors from this region, like Charlemagne’s doors for his chapel in Aachen, or the ones of bishop Willigis for the cathedral in Mainz (burnt down in 1009), were simple bronze plates.

Archbishop Bernward visited Rome several times during his lifetime. With Otto III, he visited Rome in 1001, and for some time lived on the palace of young emperor on Aventin, near the church of St. Sabina.19 It is possible that the model on which his doors were constructed, were the wooden doors on St. Ambrogio in Milan, or the ones on St. Sabina in Rome, both dating from the IVth century.

It appears that the doors were worked on by several artists, but were designed based on a drawing made by only one artist, or one of the sculptors. It is apparent that the person who designed it knew the cycle of the Book of Genesis quite well, from the Bible made in carolingian school in Tours, which is visible from the figure alternation, stylish trees, and vertically set scenes. He was also familiar with the cycle of the New Testament, like the one for example in Codex Egberti.

The doors are made of sixteen fields, eight of which on each side. One wing displays the scenes from the Book of Genesis, and the other scenes are from the life of Christ. Both wings show great influence of miniature cycles, alluding on the long carolingian tradition, with a low sense of space, not just in the organization of a scene, but also in the way the upper parts of the form are driven three-dimensionally into space, and the various plans on the surface of relief. As in all copies of late-antique and carolingian models of Otto’s period, the forms have become more compact, prolonged, rough in contures, and, although a slight progress was made in discerning the main and side characters in the scene, the tension between the characters is much more emphasized (i.e. in the scene of Encounter of the Christ and Mary Magdalene after the Ressurection where the action of falling of Mary Magdalene before Christ’s feet creates „tension“ with an ascending motion of Christ). When we look at the figures, or more precisely the upper third of their bodies, which are three-dimensionally driven into space, we come to conclusion that they are influenced by the style of detached heads we encountered before on Roman monuments such as, for example, Trajan’s column.

The doors follow a strictly organized iconographic program. On the left side there are eight panels with displays from the Genesis, from top to bottom those are: Creation of Eve, Introduction of Eve to Adam, Temptation, God accuses Adam and Eve, Exile from the Garden of Eden, Adam farms the land, and Eve raises children, Offer to Cain and Abel, Cain murders Abel. On the right side the displays are read in reverse order (bottom to top), and they display scenes from the life of Christ. Those are: The Annunciation, The Birth, Adoration of the Kings, Apparition in the temple, Christ is taken to Pilate, Nailing to the cross, Three Mary’s on the grave and Noli me tangere. These narrative displays from the Old and New Testament are symbolically interconnected by a horizontal line. For example, the scene where God takes Adam’s rib to create Eve is horizontally lined with the Christ’s apparition on the grave after Resurrection, which alludes that the spirit gains back material form.

Augsburg Cathedral

These doors were located on the southern portal, but today they are preserved in Diocesan museum, and are replaced by modern bronze doors made by Max Faller, set up in 2000. They consist of thirty-five fields, each one containing one figure, eventhough several figures (or fields) make an individual scene, so their reading is sometimes quite difficult. One side displays scenes from the Old Testament: the creation of Eve and her Introduction to Adam, Garden of Eden with the snake, Moses turning his cane into a snake, Aaron’s miracle with the canes of Egyptians, Samson killing the lion, and Samson and the Philistines. The other side displays parables from the New Testament: Woman that lost a piece of silver, Paradise birds, Winegrower; and the Christ’s ancestors from the Old Testament, including Melchizedek, Moses, Aaron, David, Judas Maccabeus and the prophets.

These doors were located on the southern portal, but today they are preserved in Diocesan museum, and are replaced by modern bronze doors made by Max Faller, set up in 2000. They consist of thirty-five fields, each one containing one figure, eventhough several figures (or fields) make an individual scene, so their reading is sometimes quite difficult. One side displays scenes from the Old Testament: the creation of Eve and her Introduction to Adam, Garden of Eden with the snake, Moses turning his cane into a snake, Aaron’s miracle with the canes of Egyptians, Samson killing the lion, and Samson and the Philistines. The other side displays parables from the New Testament: Woman that lost a piece of silver, Paradise birds, Winegrower; and the Christ’s ancestors from the Old Testament, including Melchizedek, Moses, Aaron, David, Judas Maccabeus and the prophets.

Only a few scenes from the doors can be identified as of unambiguously biblical context. Those are: Samson killing the lion, Samson and the Philistines, and the two scenes from the Book of Genesis. Other show priests, kings, soldiers, women feeding birds, people eating grapes, centaurs, lions, snakes, bears. Ten out of thirty-five panels can be considered duplicates, although they weren’t cast out of the same mold.

Conclusion

Large number of doors we find in Italy, and dating from this period, were actually crafted in Byzantium. Even if they were made in some Italian city, they were made under great byzantine influence.

The other group of bronze doors, two of which are mentioned here, originates from the north of Europe. Those are the doors from Hildesheim and Augsburg. They present some new techniques of bronze object craftsmanship (casting using the technique of lost wax), as well as a new tendency in displaying of the human character. This fact makes Bernward’s doors from Hildesheim one of the most valuable bronze objects in general.

Although some doors feature relief figural motifs, most of these reliefs are still mainly rather shallow. The model for these reliefs is an unusual one – illuminated manuscripts. Thereby, the biblical scenery and characters are transferred from painting to sculpting medium, creating a new artistic expression on the bronze doors.

Today, the medieval bronze doors are preserved in a relatively small number. The reason for this is that through history metal objects were particularly apt to destruction, because they were often melted. The obtained material was used for new objects or more often – weapons. The craft of bronze doors will continue in the following period, and some of its most famous and significant samples will appear in Renaissance.

- Most of the bronze doors of this period are found in Italy, made the Byzantine masters.

- The medieval objects made of metal, often were not preserved. They would be melted and obtained material was used to create new items or weapons.

- On the bronze doors of Hildesheim is one of the earliest examples of almost three-dimensional human figures in the Middle Ages.

- JOHN BECKWITH, Early Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque, Thames & Hudson, 1986.

- HERBERT BLOCH, Origin and Fate of the Bronze Doors of Abbot Desiderius of Monte Cassino, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 41, 1987., 89-102

- BONAVENTURA DUDA, JERKO FUĆAK (prev.), Novi Zavjet, Kršćanska sadašnjost, Zagreb, 2004.

- ROBERT G. CALKINS, Monuments of Medieval Art, Cornell University Press, 1979.

- KENNETH J. CONANT, Carolingian and Romanesque Architecture 800 to 1200, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art Series, 1992.

- MARGARET ENGLISH FRAZER, Church Doors and the Gates of Paradise: Byzantine Bronze Doors in Italy, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 27 (1973), 145-162

- DUARD W. LAGING, The Methods Used in Making the Bronze Doors of Augsburg Cathedral, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 49, No. 2 (1967.), 129-136

- (ur.) ROLF TOMAN, Romanesque, Ullmann & Könemann, 2007.

- 1 ROBERT G. CALKINS, Monuments of Medieval Art, Cornell University Press, 1797., 103.

- 2 (ur.) ROLF TOMAN, Romanesque, Ullmann & Könemann, 2007., 354.

- 3 (ur.) ROLF TOMAN (bilj. 2), 354.

- 4 (ur.) ROLF TOMAN (bilj. 2), 354.

- 5 MARGARET ENGLISH FRAZER, Church Doors and the Gates of Paradise: Byzantine Bronze Doors in Italy, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 27 (1973), 147.-148.

- 6 MARGARET ENGLISH FRAZER (bilj. 5), 148.

- 7 MARGARET ENGLISH FRAZER (bilj. 5), 152.

- 8 MARGARET ENGLISH FRAZER (bilj. 5), 152.

- 9 As shown links between the themes and teachings of St.. Paul’s statement may serve St. John Chrysostoma who said that St. Paul himself has the characteristics of the prophets, patriarchs, apostles and martyrs.

- 10 MARGARET ENGLISH FRAZER (bilj. 5), 155.-156.

- 11 MARGARET ENGLISH FRAZER (bilj. 5), 158.-159.

- 12 MARGARET ENGLISH FRAZER (bilj. 5), 162.

- 13 HERBERT BLOCH, Origin and Fate oft he Bronze Doors of Abbot Desiderius of Monte Cassino, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 41, 1987., 89.

- 14 With this theory only Margaret English Frazer disagrees.

- 15 HERBERT BLOCH (bilj. 16), 92.

- 16 KENNETH J. CONANT (bilj. 14), 127.

- 17 KENNETH J. CONANT (bilj. 14), 127.

- 18 JOHN BECKWITH, Early Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque, Thames & Hudson, 1986., 145.

- 19 KENNETH J. CONANT (bilj. 14), 128.

Interesting overview of bronze doors of the Romanesque period. I know that the Hildesheim doors were single-cast pieces…I wonder how many of the other doors listed here were as well.

According to my knowledge, the Hildesheim doors are the only single-cast piece of the doors listed here.

pretty pretty

You forgot the door of the cathedral of Salerno. You can see some photos of it in my post here

http://vacation-travel-talk.blogspot.com/2009/11/bronze-door-of-cathedral-of-salerno.html

There is a bronze door in Atrani from the same series of the 7 bronze doors made in Constantinopoli, and the door of Ravello was made in Apulia.

Amalfi (1057)

Montecassino (1066)

S.Paolo f.l.m. (1070)

Monte S. Angelo (1076)

Atrani (1087)

Salerno ( 1085- 1090)

Venezia (1120)

I truly appreciate this post. I’ve been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thanks again! keefekebaece

Awesome article.

An interesting overview. However it’ worth adding two interesting examples from Poland. That is Gniezno Door (Drzwi Gnieznienskie) with a rare if not unique iconography depicting historic scenes from life of Saint Wojciech (Gniezno Cathedral), the second example: Plock Door (drzwi plockie), originally in Plock Cathedral, commisioned and funded by Plock bishop Alexandre of Malonne, cast in Magdeburg, then transfered to St. Sophia’s cathedral in Novgorod, Russia. With biblical scenes, portraits and historical inscriptions. Both doors are from late 12th cent.

Is there any literature generally touching upon the history of medieval bronze doors?

Hi Rouben,

This is literature used for our article. Hope it helps.

– JOHN BECKWITH, Early Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque, Thames & Hudson, 1986.

– HERBERT BLOCH, Origin and Fate of the Bronze Doors of Abbot Desiderius of Monte Cassino, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 41, 1987., 89-102

– BONAVENTURA DUDA, JERKO FUĆAK (prev.), Novi Zavjet, Kršćanska sadašnjost, Zagreb, 2004.

– ROBERT G. CALKINS, Monuments of Medieval Art, Cornell University Press, 1979.

– KENNETH J. CONANT, Carolingian and Romanesque Architecture 800 to 1200, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art Series, 1992.

– MARGARET ENGLISH FRAZER, Church Doors and the Gates of Paradise: Byzantine Bronze Doors in Italy, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 27 (1973), 145-162

– DUARD W. LAGING, The Methods Used in Making the Bronze Doors of Augsburg Cathedral, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 49, No. 2 (1967.), 129-136

(ur.) ROLF TOMAN, Romanesque, Ullmann & Könemann, 2007.